How’s your relationship between work and life? Does your attention get divided between the two in a way that works for you? In this episode, Janine Hamner Holman sits down with Dr. Tracy Brower, a PhD psychologist studying work-life fulfillment and happiness, to discuss how we balance attention between work and life.

GUEST: Tracy Brower | LinkedIn, Instagram

HOST: Janine Hamner Holman | Janine@JandJCG.com | LinkedIn, Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter

What am I paying attention to this week? Earlier today I got off a call with a client who has an opportunity to bring an employee back.

The employee left back in August and has gotten in touch because they are interested in coming back. This employee left chasing payroll, chasing salary, chasing money, and he’s not happy in the new organization.

It got me thinking about paying attention to how the amount of money we make does not equal the level of happiness we experience at work, which brings me right to our guest for today.

Dr. Tracy Brower is a PhD psychologist studying work-life fulfillment and happiness. She is the author of The Secrets to Happiness at Work and Bring Work to Life. She’s also the vice president of Workplace Insights for Steelcase and a contributor to Forbes and Fast Company.

Her work has been translated into 18 different languages, and you can find her at tracybrower.com, LinkedIn, or any of the usual social channels. You can connect through the show notes. Welcome to the show, Tracy.

Thank you for having me.

You’re so welcome. As I often start with guests, what is something you have been paying attention to that other people may not be paying attention to, and what’s the cost to us of that inattention?

Oh, such a good question. I have been paying so much attention to the value of work. We have this narrative going on right now about how less work is more, and the best situation is no work at all, and the best life is sitting on the couch eating bonbons.

Work is such an important part of how we express who we are and our talents. I think we’re missing that. I think the narrative is doing us a disservice. If we pay attention to making work a better experience, that is a really wise and wonderful thing for us as individuals and as a society.

I agree as I am on a mission to have the world of work be one in which everyone can thrive. I want to dive in with you with this idea that’s been coming up a lot especially as we maneuver through COVID-19 and people have been working from home.

Of course, many people were not able to work from home, but many were able to work from home. Now organizations are trying to figure out “How much do we have people working from home and not?” With the whole diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging movement, this idea has come up around bringing your whole self to work.

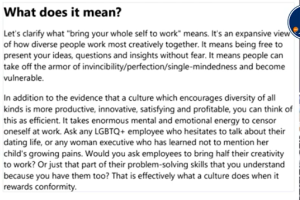

There are talks about “What does it mean to bring your whole self to work?” And what is called out is, it means being free to present ideas, questions, insights without fear. It’s interesting though that over time this has become less about this sort of connection to psychological safety, which is ultimately what that is about.

It’s now more about people not having to code switch, people being fully able to fully express all parts of their personality at work. I have a bit of a challenge with that concept, and I want us to dig in a little bit to that.

Yeah, you are the one asking this question and I think it needs to be asked. I don’t think a lot of other people are paying attention to this, so thank you. I think this has everything to do with a balance between individual needs and the needs of the team or the group or organization.

We used to talk about rights and responsibilities, and we used to talk about “My rights end where yours begin,” right? And I think there’s this really important way we need to be sensitive to others. Yes, we want to bring our whole selves. We want to not worry so much about guarding or protecting or playacting. We want to be able to be fully ourselves.

The balancing act there is being really respectful of others as well. The more we can respect each other’s differences of opinion, the more we can learn from each other. The more we can improve, the more we can really move forward together.

That doesn’t mean me giving up who I am, it doesn’t mean me compromising my fundamental identity. It does mean having so much respect for people around me that I’m bringing the right amounts of myself so we can still kind of each do that and be fully ourselves within the parameters of the relationship.

It’s hard to say what that boundary is. So you can probably say it better than I can.

My husband is a huge sports fanatic and sports are a huge part of who he is. Sometimes when he’s working with clients, he’s in the financial services industry. Sometimes when he is working with clients, he might use a sports analogy.

Even that is one of those things that can be seen as exclusionary because all the people who don’t care about sports or don’t understand what it would mean to be talking about the left tackle doing whatever a left tackle does. I have no idea. I have no idea what a left tackle does, but I know that there’s such a thing as a left tackle.

So we do want to be conscious and careful. There’s an alternative to bringing your whole self at work. Let’s all bring only, or at least primarily the worky parts. So the parts that care about how things are at work, the parts that really want to think about how do we collaborate well together, how do we connect well together, how do we communicate well together.

If we bring those worky parts, I might have a wife and if it’s cool and okay for me to reference my wife just the same way as I’m able to reference my husband, that’s part of what we’re talking about when we are able to bring our whole selves to work, because of course, so my husband also happens to be a Black man and a very dark-skinned Black man.

He can’t pretend, he cannot pretend that he is a Norwegian 6’3” white man. That’s just not something he could pretend. I however could pretend that I’m straight if I’m gay. There are all kinds of parts of our personality we have unfortunately over the last decades been encouraged to keep at home.

I think those are really the parts of our personality and the things that are fundamental to who we are as people that we want to be able to express at work. It’s all the other stuff. You know, you don’t want to know many parts about me. I am not bringing my whole self to work.

We want to be really clear, and as you said, it’s tricky when we try to talk about “What is organizational culture?” It gets sort of squirmy and squishy and just like organizational culture, which is something that each organization gets to define for itself.

Bringing your whole self to work, I believe must be something that an organization defines and is very clear on. What are your thoughts about that?

Yeah, I love this. I absolutely believe we need to be clear about who we are, about what makes us special and unique. We need to be able to express that and we need to do that within our worky context. It’s not about expressing that for the sake of expressing it at work, it’s for the sake of context and connecting.

It’s just nice to work with people and know a little bit about them. That’s part of it. I also feel like being fully ourselves is a beautiful and important thing.

What we need to do is also make sure we’re focused on what unites us and what we have in common, what our common goals are, what our purposes are, what our line of sight is to each other in terms of the work we’re doing, the way that we need to roll up sleeves and work on something together.

You mentioned sports and there’s a really interesting body of work that talks about how people approach each other and judge each other based on identity. If you ask people to listen to an opposite side in a debate and ask them what they agree with, what they don’t agree with, how emotionally frustrated they are by the person they’re listening to who may have a different opinion, they will express a certain amount of emotion or frustration if it’s a different opinion than theirs, period.

If they’ve been told the person they’re listening to supports the opposite sports team from theirs, their level of disagreement, their level of emotional reaction, their level of negativity absolutely rises. There is this judging we tend to do if we think about things as being polarized, if we start out by assuming we’re on different teams.

I think we need to be fully ourselves and appreciate others for being fully themselves. Then remind ourselves of all the ways that we are united, all the things that make us human together. Those will take us a really long way in terms of how we get things done and how good we feel about what we’re doing in the first place.

This idea of how good we feel about the work we’re doing and those things that unite us, it’s actually incredibly important to the bottom line. One of the things where organizational leaders can sometimes get confused is, well, they’re hearing all this stuff about people being fully expressed and well, “Isn’t that lovely and nice and sort of touchy-feely and whatever, but I’m the CEO or I’m the CFO, what I need to care about is our bottom line.”

The reality is organizations that are diverse, that have people from diverse experiences, diverse backgrounds, diverse educational experiences, diverse lived experiences from different parts of the country, from different parts of the world, different gender identities, all of the ways in which we are different yet united makes us way more interesting to consumers because consumers can see themselves in our organization. It makes us be able to position much more effectively because we’re thinking about all of those different components.

I mean organizations, there have been many studies, organizations that are more diverse and more psychologically safe are 34% more profitable top line and bottom line than organizations that aren’t.

Yes. Because we can bring all of the elements of our different skills and talents and perspectives and that helps us innovate. It helps us be extraordinarily better at performing. That happens at an individual level and a team level.

There is actually a great psychological study that looks at when people feel like they’re more able to just be totally who they are, when they’re more able to be open about what makes them unique, they actually perform better and organizations perform better when they can debate and dialogue.

The other thing that I’ve been really paying attention to is the extent to which we are unable to disagree with each other as well as maybe what we used to. I believe it’s so important to invite differences of opinion, to invite the dissenting voice, to ask somebody in a meeting, “I’ve just given my opinion, how do you see it differently?” Because that is the way we progress forward.

The thing that scares me is the extent to which we are no longer comfortable to do that because we don’t want to offend anybody or the extent to which people are offended if they hear an opinion that’s different than their own. But we need to be able to put things forward that disagree with our own point of view. That’s the way we move forward.

That’s part of where that data comes from, that you suggested when an organization can disagree and move things forward and learn from each other, that is what will make them a better performing organization. That will actually make more of us happier as well. We get to learn, we get to be challenged, we get to feel closer to others because we’ve learned something more about their opinions as well.

I think we are at this really interesting and challenging moment in time where the idea of civility and civil discourse has sort of fallen out of our thinking. One of my very best friends is getting her doctorate in community engagement and polarization.

This idea of being able to communicate and have differences of opinions and when we have differences of opinions, sometimes we get hot about it. So letting people fully express, sometimes get hot about it, then if feelings get hurt or if things happen through that process, then having ways for people to come back together again. I’m working with an organization right now where their leadership team has gotten fractured over some things that were said and done.

Part of what we’re working on is humans are humans, and sometimes we say and do things that aren’t great. Then we get to own that and apologize for it. We’ve got such a frame in our society of “Never apologize, never say you’re wrong, love is never having to say you’re sorry,” as far as I say, b%!!sh*t to all of that.

And we haven’t talked about Brené Brown, but my hunch is you may be a Brené Brown fan and one of her quotes, which I wish I could find again, but it is something like “That thing that you are most afraid to show other people is the thing that makes other people interested in you. That thing is vulnerability.”

When we get vulnerable, when we are able to share of ourselves, when we are able to say, “I don’t know,” or “Man, I messed that up,” that’s when other people lean in and that’s when they get interested in us. That’s when true connection can be made.

Yes, exactly. I’ve been thinking a lot about critics because there’s all the curfuffle right now about how Elon Musk shot down a few prominent journalists because they’re critical of him.

I’m working on an article right now about the benefit of listening to your critics, of being open to your critics because you learn and you can continuously improve. You learn what’s out there and you may disagree with it, but it may help you learn about your own perspective and improve, but it also helps your credibility.

When you listen to your critics you lean into, “I am strong enough in my beliefs, I can share data, I can be open to other opinions, I can shift when I get new information.” But also to your point, it builds trust because when we’re able to be vulnerable and open to other people, that is very trust building.

I did an article last weekend about social media and one of the problems with social media is the algorithms work too well. Then we get echo chambers. The problem with an echo chamber is I start to believe that most of the opinions out there are similar to mine.

Then everybody thinks what I do. If everybody thinks this, we must all be right.

We’re all brilliant, right? Social media also shuts down the opportunity for nuance and understanding. To your point, particularly at work, it’s a great context for us to understand nuance, for us to ask questions, for us to express our vulnerabilities, for us to be open to the thing somebody said that was really not said very well and kind of made us mad, but we’re going to keep the relationship moving forward.

There’s a wonderful example of a gentleman who runs a museum in West Michigan, and it’s a museum of African-American and Black pop culture. It’s got all the negative and really offensive examples of how Blacks and African-Americans were exemplified in culture. He talks about how important it is to learn from those examples.

He talks about when they invite people through the museum, they ask people to react and respond in dialogue. A lot of times people do not express themselves well. They’re really imperfect about expressing themselves.

But he said, “If you ask for input, if you ask for opinion, you have to be open to people expressing themselves badly and still being open to listening and learning,” and heaven knows, that’s the scary thing for all of us. We want to do the right thing by each other. We want to express appropriately, and we’ll never be able to do that perfectly.

I think part of civility, part of trust, part of leaning in like you’re talking about is asking for feedback and being open to learning and saying, “I sure don’t have this figured out, but I would love your help on it.”

Right? I want to make the connection in our last segment of this to what’s being called psychological safety at work. Amy Edmondson is the author of The Fearless Organization.

Part of what I love is before she became a household name–so there are cards that I send out to thank people. On the back of the card is a quote from Amy Edmondson that I found in another book because one of the things I love and one of the things she loves is brain science.

She says “We have a place in our brain that’s always worried about what people think of us, especially higher ups as far as our brain is concerned. If our social system rejects us, we could die given that our sense of danger is so natural and automatic, organizations have to do some pretty special things to overcome that natural trigger.”

That is part of what got her into thinking about “How do we create an organizational culture in which people feel safe, in which people can bring their whole selves to work, their authentic selves to work?” I want to make the connection between this idea of psychological safety and this idea of bringing your whole self to work.

Yes. Psychological safety is so much on our radars right now. Interestingly it started with the dialogue about safety. We were thinking about air safety and surface cleanliness and safety way more in the last two years than we probably did in the last 20. I don’t know, I might be exaggerating a little bit.

I don’t think so.

That led us to “what do we really mean by safety and what is psychological safety?” It’s important that people feel like they’re safe, people are going to back them up. They can take a risk, they can make a mistake, they can do the dumb thing and have somebody pull them aside and say, “I need to give you some feedback about that.”

My very first boss was just brilliant and amazing. He used to talk about feedback as a gift. When somebody gives you feedback, they’ve actually had to take a risk in order to do that. When they pull you aside, that is absolutely a gift to you.

It says they care enough, they see what your goal was overall, they care enough to pull you aside and they care enough to give you some ideas and some reflection and some alternatives. The thing I always like to compare is the relationship of psychological safety and comfort and discomfort.

Think of psychological safety on a vertical axis and comfort and discomfort on a horizontal axis. Discomfort can be a really good thing, right? It’s the thing prodding us and asking us to think differently and pushing on us, “Oh my gosh, we’ve got a lot to learn.”

When we have a high level of psychological safety, we feel like somebody’s going to back us up. We feel like we can bring our weird sense of humor. We feel like we can be fully ourselves, and we have a high level of comfort. That’s when the greatest growth and innovation happen.

But ironically, the more psychological safety you have, the more open, free, and liberated you feel to take risks. The comfort that you get from psychological safety helps you to be open to the discomfort of trying something new, raising your hand for the new initiative, expressing an opinion that might be unpopular, but can help move the organization or the team forward. So I really like the relationship of psychological safety, comfort, and discomfort.

I love that too. One of the things that we have been collapsing is this idea of safe spaces and psychological safety. There are organizations I believe have gone a little too far on the spectrum so people have the opportunity to say, well, “This conversation is making me feel unsafe, and I’m opting out.” What they mean is “This conversation is making me uncomfortable.”

When we have the foundation of psychological safety, when we know this is a safe place in which people can be brave, then we can get comfortable being uncomfortable. There’s a big difference between feeling unsafe and feeling uncomfortable. We get to help parse that out for people because I think we are often collapsing those two different ideas.

Yes, absolutely. You said it, it’s the foundation. A foundation of trust, a foundation of respect, a foundation of absolute psychological safety that allows us to be curious or push back or ask each other the hard question. But we need that foundation.

I think to your point back to civility. Civility and the way we behave toward each other is part of what builds that foundation from which we can build in terms of the way we take risks and innovate together.

Essentially it’s not creating a safe space in which I can express my homophobic ideas or my misogynistic ideas or my racist ideas. It’s a space we are creating where my rights and where your rights begin and we are being respectful and civil with each other.

What we are doing is we are creating a space where I can be curious and I can ask important questions. I mean, it might be that I come from a place that is all of those things. I might have a perspective that I could bring.

Well, some people out there in the world might have the perspective of this, “If it’s relative to how we’re positioning ourselves as an organization or relative to how we’re marketing or relative to how we’re branding ourselves as an employer, or how we are selling the widget that we sell or whatever it is.

So I might be able to bring that perspective if it’s going to help move a conversation forward and know that it’s going to make people uncomfortable. In that frame, I would want to soft step my way into it. I’m going to say something now that may make people feel uncomfortable, but I feel like it’s important for this conversation.”

Then what we’re doing is we’re having our worky self, our worky parts of ourself, our worky parts of our brain, be able to express something that may not be politically correct, but that I agree with, and I don’t, but were I to be that person, then we would be having a conversation about how to move the organization forward and people know it may get a little charged. When you create that frame, when you create that context, I think it’s helpful if you’re going to do or say something that may stir the pot a little bit.

Yes. Creating that frame and that context, which for me is about sensing and being sensitive. You’re sensing the environment. You’re reading the room. “I know this might be difficult and let me just put this out there.” You’re being sensitive to others. I think the word that we haven’t used yet, which is so relevant, is empathy.

We’re really meeting people where they are and thinking about “How might they be thinking or feeling” and being really respectful of, “Gosh, they might have a really different perspective because they had different experiences. They come from a different place.”

The other thing I think is worth saying is there’s some wonderful research on happiness and the extent to which your happiness is significantly greater when you’re thinking about others and about the community.

When we’re focused on ourselves, “Am I happy? What makes me happy? How do I get more happy? What do I need to do to be happy?” You will actually detract from your own happiness.

When you’re thinking of others, when you’re thinking about how you contribute, about how you have an obligation and responsibility to other people, that is positively correlated with happiness. That is the thing that will help us find that balance.

When we think, “I’m going to be fully myself. I’m going to bring myself, I’m going to embrace my identity. I’m going to share things that might be tough for others, but I’m going to do that in a really sensitive way, in an empathetic way. I’m going to frame that to your point, I’m going to demonstrate civility because that is also my responsibility to the community.”

That will help us to all have a better experience. It contributes to happiness at work, which is absolutely connected with business results.

Absolutely right, full circle. I want to end and then have a slight opportunity to talk about it, because it’s a little bit of a cautionary tale.

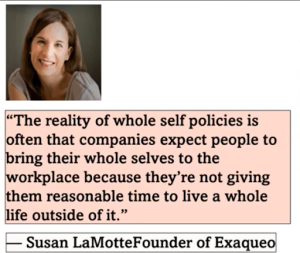

Sometimes organizations use this idea of bringing your whole self to work because they’re not giving people enough time to be a whole human. They’re not giving people enough time to be outside of work. I wanted to know if you’ve thought about that challenge at all, because that was sort of a new frame for me. I was like, “Huh, I wonder if we’re being naughty sometimes and using this in a different context.”

What an interesting frame, right? What I go right to is when there’s a spillover effect, when we’re happier inside of work, we perceive ourselves to be happier all over the place. That’s not news for any of us. The news is that when you’re happier outside of work, you tend to perceive greater happiness inside of work.

It’s a great idea to go do the thing you love to do with your family or friends or volunteer work. It’s great when companies want to create places where we want to bring our families in and have them visit or have affinity groups which help us connect or have dry cleaning on site or meals that I can order in when I’m working late.

All those are great, and we don’t want to send a message to people that this is the only place there is and we want you to give 150% so you’re totally sapped out by the time you get someplace else.

It is a good point that when we give people the opportunity to be fully themselves outside of work, that is actually the condition for people to be more fully themselves inside of work, to bring their whole selves because they’ve got energy and they feel fulfilled and they feel more full. Their tank is more full so they can bring that when they’re in their worky mode.

I love it. Thank you so much, Tracy, for being here with us today, for sharing your insights, for sharing from your body of work. I really appreciate you being with us. Thank you so much.

Thank you. I really appreciate it.

This has been The Cost of Not Paying Attention. Remember, great leaders make great teams. Until next time.

Important Links

The Secrets to Happiness at Work

About Dr. Tracy Brower

Dr. Tracy Brower is a PhD psychologist studying work-life fulfillment and happiness. She is the author of The Secrets to Happiness at Work and Bring Work to Life. She’s also the vice president of Workplace Insights for Steelcase and a contributor to Forbes and Fast Company. Her work has been translated into 18 different languages.