When was the last time you had a conversation about a serious subject, and you felt understood? How do you communicate to help people feel validated? In this episode, Janine Hamner Holman sits down with Leigh Chandler, a mediator, to discuss how we have conversations, ask questions, and help each other feel heard and understood.

GUEST: Leigh Chandler | YouTube

HOST: Janine Hamner Holman | [email protected] | LinkedIn, Facebook, Instagram

What am I paying attention to at the moment? I had the neatest experience yesterday. I was having dinner with a client and we had all gotten together the previous week. We’re working on mission, vision, values for their company.

This company has been around, it’s a family-owned business. Grandpa started it, then dad took it over. He’s now in his mid-sixties starting to think about not retiring, but sort of backing off.

He wants to get a lot of the things that have enabled him to grow the company so much since he inherited it from his dad in place, to be part of the formal organizational culture before he steps back some.

We’re looking at values, what got the company to where it is and what we want the values to be of the company going forward. It connects to the podcast episode we did recently with Corey Castillo.

When we were having dinner last night, the son of the dad who is semi-retiring said to me, “Janine, when you were talking about health and you were talking about mental health, you said something that I had never heard before and it helped the conversation around mental health land with me in a whole different way.” We were talking about health as one of the potential core values of the company.

I’m going to share what I shared with them, which is, I am on a campaign to normalize mental health issues. If I fall down and I break my elbow or hurt my knee, I don’t have a problem telling you about that.

I don’t have any shame maybe other than the fact that I’m a klutz, that I fell down. Other than that, I don’t have an issue telling you about the fact I hurt my knee.

On the other hand, if what I hurt was something inside me, like my feelings or my dignity, or I suddenly didn’t feel safe because of something going on, or I no longer felt like my opinion mattered, or like I belonged, or I’m dealing with stuff in my family or with my friends, and I’m struggling with depression, we have a whole other set of conversations.

We have a whole other set of stories that come into play at that point. I believe there should be no difference between me telling you that I fell down and I hurt my knee versus there’s something going on with me internally and I’m feeling depressed, or I’m feeling anxious at a level where I’m feeling like I need to get some help. I need to get some support around that.

May is mental health awareness month. I firmly believe when we can get our mental health issues out of the shadows, when we can destigmatize our mental health as a society, as a community, we have so many more possibilities and opportunities for connection and thriving.

That brings me to our guest for today. Our guest is Leigh Chandler, and she is a mediator who resolves conflict between people who are stuck with each other. Before you close the company, break up the band, or cancel Thanksgiving, call Leigh.

Leigh, welcome to the show.

Thank you so much for having me.

You’re so welcome. I’m so glad to have you here. I’m going to start the way I often do, which is tell me something you have become aware of we are not paying enough attention to, and what’s the cost of that unawareness?

As a mediator, by the time somebody gets into my office, they’ve been in conflict for a while. They’ve had a lot of conversations about that conflict and it’s not going well. You don’t end up with me if your conflict is going well. It has escalated if you’re sitting with me. One of the things I get to hear about from people are those other conversations they had before they got to me. I get to see the influence those conversations had on escalating the conflict.

I don’t think we pay enough attention to the impact we have on our friends, our family, our coworkers, and our clients and customers depending on what industry we’re in when they come to us and tell us about a major or minor conflict they’re having with another person.

We have a lot of power in those situations and I don’t think we learn how to use it. If you’re not able to be a helpful listener in those situations, the cost is people end up breaking relationships, they break up businesses, they end up in litigation. Best case scenario, they end up with me, but a lot of them end up in court and it’s a huge cost.

I love that we’re talking about this. I love it especially because the way I know, from knowing you, that you approach this stuff by understanding the role stories and stories our brain makes up can create some mischief. Tell me more about how all this works in your experience.

I see two main types of unhelpful listeners people tell me about.

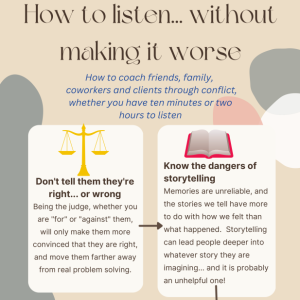

One of them is the cheerleader. We all love our cheerleaders. Your cheerleader tells you you’re right, you did everything correctly, and the other person is awful. They do it with the best of intentions. They want you to feel better, they want you to like them, they want to be supportive and helpful, and they’re not helpful.

The other type of unhelpful is the devil’s advocate. That person argues with you, challenges you, and tells you what the other perspective is. They also usually have good intentions. They have a great outside perspective, and they want to prevent you from making a mistake. They want to expand your thinking, and they’re also not helpful.

The person with the cheerleader gets to me in mediation, believing their story 1000%, not at all curious about other perspectives and with a feeling like their story needs to be right in order for people to sympathize with them.

The person with the devil’s advocate often, in conversations where they’re being challenged, they feel they’re not being listened to, they’re not being understood. They’ll start to exaggerate or embellish their story, and they often don’t realize they’re embellishing. They’re doing it to try to get their listener to sympathize with what they’re feeling.

By the time they get to me, they believe this completely made up story. To talk about stories, one of the things I tell people is to recognize the danger of letting someone’s story tell for too long. This goes back to what you were saying about mental health.

We will tell a story about what happened in order to describe how we feel. A lot of times I think that’s because people are uncomfortable directly saying, “I just felt bad.” They don’t think they’ll be taken seriously if it’s about their feelings.

They’ll exaggerate the mean thing the other person said to them in order to express they felt hurt. If you let them keep telling that story, they believe it, because we believe our stories as if they happened, we react to them emotionally inside, like they happened. There have been so many studies about how unreliable memory is. In mediation you see that, because I’ll have two people, they’ll tell me two different stories. They’re both telling me the absolute truth is they understand it.

As their truth. I love how much we have evolved in our understanding about memory. It used to be, in court you would bring in all the eyewitnesses, and they would give you their eyewitness testimony. That was what we went by because of course these people were there, they know what actually happened.

What we have discovered along the way is eyewitness testimony is relentlessly untrustworthy because we change the memories in our brain without knowing it. There’s a gentleman who has now passed on, by the name of Marcus Borg. He’s a religious scholar and he’s from Ireland, but he spent the majority of his adult life here in the United States.

He used to talk about, when he remembered learning how to drive with his dad sitting beside him, his memory is that he’s sitting on the left side of the car and his dad is sitting on his right, except this was happening in Ireland where he knew intellectually he would’ve been sitting on the right side of the car and his dad would’ve been sitting on the left because that’s how British cars are set up.

He can’t make his memory of it flip even though he knows it’s wrong. I love that example because it’s such an easy thing and it’s something most people don’t get charged up about.

When we remember something with emotion attached to it, I love the way you phrased it, what we are remembering is how we felt. We’re not remembering the actions that were done in exact detail because it’s all colored by what was said and how it made us feel.

Depending on how disconnected or uncomfortable someone is with their own emotions, they’ll be more likely to try to construct a story justifying those emotions because they’re not comfortable saying, “I was upset and it was a little irrational.” That’s more uncomfortable for some people than others.

The unreliability of memory… if anyone has a sibling, I’m sure they’ve had the experience of having some conversation about something the whole family did. The siblings have totally different recollections of it. It’s amazing how it happens.

It’s amazing, yes. As you said, when there are emotions attached to that, whether there are emotions attached to that story or whether it’s the family dynamic that their emotions attached to, we can remember things massively differently. Then there can be, hopefully there’s humor attached to it, but often there’s sadness, anger, frustration, and a feeling of being disrespected or you not belonging or I mean… We know human beings only need three things: We need to feel safe, we need to feel like we belong and we need an experience of dignity. We need to feel respected.

When things happen that confront us in those ways… over the weekend, my husband and I were having a conversation. He said something that definitely triggered me. It wasn’t a big thing, but I felt disrespected. He came to me later, not much later at all. He did a great job. He came to me later and said, “I’m so sorry I hurt your feelings.”

That is a huge growth opportunity for him. I didn’t want to say, and I didn’t say in that moment, actually, you didn’t hurt my feelings. You made me feel disrespected. Those are different things. What I really needed to hear was he got what the impact was, but I also know we are all beings in the process of becoming. What he needed to hear was I heard and accepted his apology, even if his apology wasn’t exactly what I needed.

I got to appreciate his apology and then make a decision to let it go. I can’t tell you anymore what it was because I let it go. I think that distinction can be important, and can be tricky because we want people to understand the impact over here, and when what they apologize for isn’t what the impact was over here, we can end up escalating stuff.

What are some tricks and tools you know of that can help us when we get our feelings hurt, when we miscommunicate, when we don’t do a great job in being partners with anybody else?

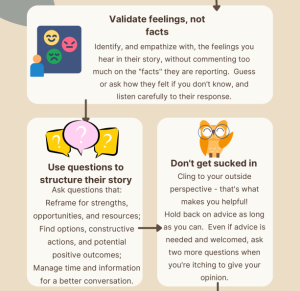

When you’re helping someone else who’s in a conflict, they always say validate their feelings so you can have a conversation about how they feel and not about what happened. When you’re directly involved in the conflict, there is a risk you validate the wrong feeling and that doesn’t go well.

When you’re the third party, you can validate the wrong feeling and it’s helpful because it can make the person explain to you how they feel. When you’re in the heat of the moment and you say, “I’m sorry, I hurt your feelings,” and in actuality they felt disrespected. That can make them feel like they haven’t been listened to again. I always recommend questions.

Questions are the thing you should do before you do anything else. The more you can explore with curiosity how they feel, and that can be uncomfortable.

When we’re in the heat of the moment, we want to do what we can to manage ourselves in that time and we want to ask questions. We want to get curious about what’s going on over there.

A friend of mine posted this great thing about asking questions and what she said was, if you are asking a question, and if at the end of the question you could insert the words, “You idiot,” it’s not a great question. If the question you’re asking is why did you throw that chair, and you could insert the word “You idiot” at the end, which you could, “Why did you throw that chair, you idiot?” You’re not setting the person up well as a great question.

If instead the question is “I can see you got triggered at that point, can you tell me a little bit more about what’s going on or what was happening for you at that moment?” It’s harder to put “You idiot” in at the end of that question.

When we’re getting curious, especially if we’re the third party, we want to be careful and conscious about how we craft the question so we are genuinely being curious as opposed to asking a question that’s coming from judgment. We want to ask a question that’s coming from genuine curiosity.

You’re talking about questions and questions are my favorite thing ever.

Yes, and curiosity.

Curiosity is hard. You have to cultivate your curiosity and you have to work on that when nothing’s wrong. If you are trying to be curious for the first time when you’re in an argument, you will fail. You need to be curious when everything’s okay. You need to be curious in every part of your life, so it becomes a habit.

I love what you just said. If you’re curious for the first time when you are in an argument, when you’re in a heated emotional situation… we don’t do great the first time.

It can be tricky, because human beings are judgmental creatures. Something happens and our brain immediately makes up a story about what it means. It’s how our brains are constructed. It’s how we learned to remember stuff before we had words, books, and the opportunity to document things. Story enabled our brain to remember.

Our brain immediately makes up stories about why you did what you did, why they did what they did, why that thing happened that way. If I got injured in some way, if I felt unsafe, if I felt like suddenly I didn’t belong, if my dignity got impacted, then I’m going to come at that story from the place of judgment. There’s going to be a lot of judgment over here about what you did because of how you made me feel.

As somebody who is supporting other people in that situation, if I’m a manager and one of my employees comes to me with an issue, or I’m a family member to someone who is struggling, but I’m not the one who was in the situation, what’s the best course of action? How can we be a good listener? How can we be a good partner to the person who’s coming with an issue?

The first thing is exactly what you said, you need to be non-judgmental. The best way to be non-judgmental is to be aware you’re hearing a story and it’s not necessarily what happened, and it doesn’t matter if it’s what happened because they’re telling you how they feel.

If you can keep that in your head, it helps you keep that judge to the side. You’re never going to completely eliminate the judge, but you can make it a voice you recognize and maybe don’t act on. The next thing is to validate their feelings, but don’t tell them that they’re right or wrong about what they’re saying. When they’re saying the guy in the next cubicle microwaves tuna in the break room and it stinks and I hate it, you don’t say, “Oh my God, I hate that too.” Even though you do.

You say “That must be unpleasant and distracting while you’re trying to work.” It’s a slightly different statement, but it gets them talking more about how they feel and less about how much they can’t stand the other person.

Why is that important? Why is that an important distinction?

Because if you start validating the facts, you get them more set on the idea their story is correct. You get them into a situation where they feel they need to give you a fact to make you understand them.

Then, when they want you to understand how upset they are, they’re going to embellish that story about the other guy. Then they’re going to believe their embellished story about the other guy. All you’ve done is escalate things for them, even though in the moment they will probably feel better and think you are a good listener.

That’s so smart, because again, what they’re telling you is a story about how they feel, not a story about what actually happened. When we focus on the details of the story, the details of what in their mind are the things that happened, especially if there were heightened emotions involved, they’re going to become more invested in that story about what actually happened when it may not be what actually happened.

You might find out this person is stressed out and distracted for a dozen reasons. The microwave problem is one of them, but it’s not the most important one. If you can get them talking about how they feel, you can often find the problems that need to be solved. That doesn’t mean the problem they came to you with doesn’t need to be solved. It is, however, often the tip of the iceberg and it’s easy to focus on it because it’s what came to you and you don’t get to see underneath, to see what’s really going on.

This is from a graphic you use when you’re helping people think through this. In this section here under asking questions, what are some examples you can help us think about that might be great for how we can find the most effective frame to help move the conversation forward?

I like to look at where someone is stuck. You can often see that early in a conversation, you can see they’re feeling like a victim, for example. If that’s where they’re stuck, in this victim story, then you want to ask questions that empower them because they can’t move forward with problem solving until they’re empowered.

If you tell them they’re not a victim, they feel like you’re attacking them. You want to ask questions to make them feel like they can do something. I like to ask, “What have you done so far to try to solve this problem?” It gets them talking about things that didn’t work, about constructive actions they took.

It can be helpful to ask if they’ve ever dealt with anything like this before and what they did in that situation. You want them to tell you some kind of success story, and then give them some praise. It can make them feel like they have the power to do something.

Often, someone who’s feeling stuck in a situation isn’t able to look at other options. You should ask questions that get them to do some option generation. If someone’s stuck in a job they hate and they feel like they can’t get out, everyone they work with is awful, and their boss is awful, you can ask a question along the lines of, “If you could have a different career right now, what would you want to do?”

It can get them talking about passions and thinking about things outside of what they’re stuck in. Even if it’s totally unrealistic, it changes their mindset and gets them unstuck. I like to reframe in a way that gets them out of whatever mindset they’re stuck in and into somewhere else, where we can do something a little bit more creative.

It is so easy for us to get in a victim mindset about something where we feel like we are at the effect of whatever it is that’s going on. In part, it’s such a challenge for us because when we are stuck in that place, often we are missing one or more of safety, dignity, and belonging. We might be missing all three.

When we get stuck there, as you said, we can’t be generative, we can’t come up with how we can move through this, we’re just stuck in that dirty diaper. I say to clients sometimes, “How long do you want to sit in that dirty diaper?” It’s a graphic image, but it is an image that can be helpful.

It’s an amazing image.

It can be helpful, depending on the person, in helping them move through it. If they have some level of self-awareness, their response is often, “Oh yeah, I might be ready to leave that.” One of the things that can also be tricky in this situation is, longtime readers will know, I got very interested about 15 years ago in brain science and how our brains work and what’s going on up there.

My entrance into the world of neurobiology was trying to understand dating. I was dating and interested in getting married and thinking, “What are these men doing? Is there something different about our brains, because a woman wouldn’t do that?”

It turns out there is, and one of the things that’s different is our default way of listening. Men tend, obviously, this is on a spectrum, some more than others, but in general, men tend to listen more through the lens of “What’s the point, what’s the problem?” If they care about you, then they go to, “What do I need to remember about this?”

Women tend to listen through the lens of “How do we connect through this? Are we now disconnected, threatening belonging and safety?”

The way we are socialized and biologically in our brains, the way our brains tend to process information can also be a little tricky in this domain, especially if I have a brain that has been trained to listen for “What’s the point and what’s the problem?”

What you’re saying is, the more effective way for me to listen in that place is “What was the impact on you and your feelings and how can I help you move through this process?”

Yes, and it can be hard to listen that way. The gender split you mentioned is funny because women are much more likely to be the cheerleaders and men are much more likely to be the devil’s advocate, in my experience.

Yes, absolutely. In part that’s because of how we listen. If we are listening for connection, I’m going to get on your side and say, “Oh my God, I can’t believe they did that. What a jerk, you need to get out of this situation.”

Men are much more likely to move into problem solving because they’re listening for what’s the problem, and then how can I help you solve that problem, which then often has them come from that devil’s advocate perspective.

As we are learning this new skill around listening maybe from a different place or practicing some new questions, if someone is starting out in this journey, what’s a good way to start practicing?

It’s great to start practicing when someone’s confiding in you as opposed to starting to practice when you are in conflict because you already have the benefit of being outside it and not being emotionally invested. Being able to pause before you speak is important. Everyone has trouble with it, but if you could make that the rule in the next conversation where someone is complaining about something, to pause for a beat before you respond.

That gives you the space to make different decisions, because we all have some amount of wisdom about how to interact with and help someone. We get in our way sometimes by doing the first thing that comes to mind and not taking a second to make a better decision.

The other thing, especially if you’re a devil’s advocate, before you give an opinion or ask something that’s meant to be a little challenging, because it’s not like that’s never a good thing to do. Before you do that, ask two or three more questions, and give yourself permission, “After I ask three more curious questions, I can say what I want to say.” If you ask those three questions, I promise you’re going to say something different afterwards every single time.

Because that moment when you’re itching to say your thing, that’s never the time to say your thing.

Right? Because probably you can put “you idiot” at the end of what you were going to say.

Probably, yes. Also, in that instance, what you say is about you, it’s not about them.

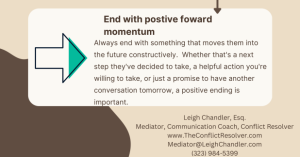

I love that. Here is Leigh’s contact information. We will also put it in the show notes for the podcast. This is also at the end of a conversation, in relation to concluding these conversations based around curious questions, we want to, when we can, leave people in a particular place. Leigh, where are we striving to leave the conversation, and leave the person in that conversation?

Endings are so important, and in listening situations often the end is overlooked. You realize you’ve gone over the time you had and you’re rushing off. I always want to leave the conversation with something positive that moves the person forward.

It doesn’t have to be you’ve solved the problem during the conversation. You probably haven’t, but at some point, if you were asking good questions, they probably mentioned something they could do, whether it’s something to resolve the situation they’re in or something to make them feel better. They might have said they’d feel better if they could go for a run today, or they think they should hold off on sending that email until tomorrow.

Whatever it is, something good they’re going to do, you can end the conversation by referencing that thing so you end it on a note where they’re empowered and doing something helpful. It can be good for them because it lets them go forward from the conversation instead of just going back into that stuck place and looking for someone else to listen to the sad story.

That’s so good. When we are telling what happened, but really what we’re telling is how it made us feel, then often we want to go tell other people that same story about how we felt. We have such a tendency, especially in our busy world, to not fully close the loop on things and conversations. When we can leave somebody in a place of forward momentum, as you say, then it’s a constructive ending to that conversation.

If there are things left open… I was with a client earlier this morning on a Zoom call, and it’s with a fairly large organization. He had 271 managers on a Zoom and the CEO was talking about what’s happening with the company, giving some updates about things, and doing a little training.

At the end of the call, there were probably a dozen people with their hands up, but he ran out of time. I thought, “Okay, we need to do a better job when that happens at the end of a conversation and acknowledge, ‘I see you have your hand up, we’ll follow up.’”

We want to leave people in that place of being seen, of knowing they belong, of feeling safe and secure, of having dignity. We want to continue to create that forward momentum in whatever we do and close those communication loops.

That’s a great ending. “I’ll check in with you tomorrow.” That’s good enough. If no other progress has been made, just that promise, “I’ll send you an email. I’ll make a phone call tomorrow, and see how you’re doing.”

Awesome. On that note, I am going to wrap it up for today. Leigh, thank you so much. Thank you for sharing your wisdom and all of your great insights about how we can help other people and ourselves, if we tell the truth, move through conflict to resolution. I so appreciate your brilliance on this topic.

Thank you. I appreciated everything you had to say as well.

Awesome. I am Janine Hamer Holman, and this has been The Cost of Not Paying Attention. Remember, great leaders make great teams. Until next time.

Important Links

About Leigh Chandler

Leigh Chandler is a mediator and conflict resolution specialist. Leigh has been a practicing attorney in California since 2007 and has helped people resolve their disputes since starting out. She specializes in conflict resolution where the parties involved can continue to work together and have a working relationship post-conflict.