When you feel grief do you know how to process it? Do you recognize it? In this episode, Janine Hamner Holman sits down with Alyssa Gioscia, an executive coach and talent development professional, to talk about the cost of misunderstanding grief.

When you feel grief do you know how to process it? Do you recognize it? In this episode, Janine Hamner Holman sits down with Alyssa Gioscia, an executive coach and talent development professional, to talk about the cost of misunderstanding grief.

GUEST: Alyssa Gioscia | Instagram, Facebook, LinkedIn

HOST: Janine Hamner Holman | [email protected] | LinkedIn, Facebook, Instagram

Welcome to The Cost of Not Paying Attention. I’m your host, Janine Hamner Holman. What am I paying attention to today? I came across a quote about how human beings, all of us, are constantly seeking safety, belonging, and dignity.

That’s a perfect encapsulation of a lot of things going on in the world today, in the world of work, but also in our lives. We’ve all been living through this COVID-19 pandemic. Now we’re getting into the place where things are a little bit more, I don’t know… normal-ish.

Yet we’re still looking for safety, belonging, and dignity because that’s what we’re wired to do. Safety in particular has been one of those things that’s hard to come by because there’s been so much in flux, so much uncertainty.

That connects to belonging because when we don’t feel like things are safe and firm, it can be hard to feel like we know where we fit in.

That connects to dignity, feeling like we are respected, like we know what we’re up to, and feeling clear on what’s going on. This has been a challenging time for us humans.

It’s also been a hard time for organizations because of this constant flux. An unfortunate reality is, all of the really smart people who study this stuff say, “Aside from COVID-19, the amount of uncertainty and change, and the pace of change, is going to continue to be like it has been.”

Our opportunity as humans who are constantly on the hunt for safety, belonging, and dignity, is to figure out how to both get clear about what is and learn some new skills around resilience so we can weather all of this. That brings me right to our guest.

Alyssa Gioscia is a certified executive coach and talent development professional. She has a real passion for guiding people toward bringing their dreams to life and accomplishing things they think are impossible.

I love that and I love her. You, readers, are going to get to experience why. She is passionate about getting to the heart of people’s stories and partnering with them to produce powerful legacies.

Welcome to the show, Alyssa.

Thank you, Janine. I’m happy to be here.

I’m going to start the way I often do, which is, what is something you have become aware of that we are not paying enough attention to, and what is the cost, in your wisdom, of that inattention?

For me right now, one of the big things we are not paying enough attention to is grief and how we process it. The cost is the unhealing we experience, when we think we’ve healed from something and we haven’t.

Grief has an interesting way of morphing into other things like anger, rage, and negative emotions that sit at the bottom of your stomach, and then fuel other things.

When you’re having another emotional moment, instead of it being only about the thing you’re addressing, it’s fueled by all of this unresolved grief that has turned into anger.

When I’m going on my own personal journey, I’ve hit a lot of different moments where I’ve found something there to grieve. It’s something we miss a lot. There are a lot of rules around grief that are not actually correct. There are rules we think we have to go through that don’t actually help us close the loop.

There’s so much there to unpack and that’s brilliant. Let’s start with when you’re thinking about grief, and when you’re working with the folks who you help create enormous breakthroughs so they can soar and create in their own lives.

When we think about the things we’re not grieving fully, in part, are those the things that happen in our lives about which we have sadness and grief? We just had to let go of our 16-year-old dog in January, and that was incredibly sad and there was a lot of grief around that.

Are you also talking about how we are living in these dynamic times of today, and grieving the way things used to be, what we used to be able to do, or how things used to work, or all of the above?

Yes, all of the above. It’s very easy to tie grief to death, which is the main thing we think about when we’re thinking, “I need to grieve this person or this pet.” We often tie it to that. But there are so many other things we need to grieve because of the unmet expectation, or the story we were telling ourselves of how it would be, could be, or should be.

All of those ideals or dreams have a moment where they can be grieved. That’s everything we’re dealing with: the job I thought I would have, the fact that I got laid off, the way my business is going differently, maybe not good, bad or otherwise, but just different, the loss of a friendship, a relationship, a person in your life.

There are so many areas, and, if I say to a client, “Have you grieved the loss of that job?” It almost doesn’t connect because the thought is, “A person didn’t die, so why am I grieving?”

There’s so much opportunity to address the unresolved feelings about the situation and how it looks different than how we thought it would turn out.

There’s so much in our lives that doesn’t turn out like we thought it would. The life I thought I would be living now when I was 5, 10, 20, or 30, has no relationship to the life I am in fact living.

Even in the way life is going right now, if you asked anyone in November or December of last year what their life would be like in April of this year, versus everything that happened in December and January to what they’re doing now, it’s completely different. If you asked me in December what I would be doing now, it would not be what I am actually doing now. That’s a big shift for most people.

Is part of it also that we, as humans, tend to get very hooked by how we think things should go? Whether it’s how this conversation should go, how this relationship should go, how our children should be, how our business should be, or how our career paths should be. Is that part of what’s tripping us up as well, that we get hooked into this “should,” which then gets tied to an expectation of how it’s supposed to go?

Yes, 100%. We love to fill in the blanks. We don’t like uncertainty because that’s where our brain thinks there’s some kind of danger. If I know A and D and F, I need to fill in B and C and close the gap. All of my clients have heard me say, “Should or shouldn’t, what is?”

Because well, I should call that person, or I should do this. Let’s take that off the table. What do you want to do? What will move you forward in a way that makes sense for you?

Oftentimes the “should” is something that we’re trying to force ourselves into that we don’t actually want to do. Even intuition-wise it may not be right. There’s also a balance of saying, “Okay, what am I doing where I’m just trying to avoid or procrastinate? On the other hand, what am I trying to force myself into that’s not right for me because it worked for somebody else, or because there’s a story that I’m telling myself?”

I had a mentor a while ago who used to always say, “Stop “shoulding” on yourself.” I thought it was funny, but also perfect because that is what we do. We create these expectations and “shoulds” and then we put them on ourselves. It lives, often, like something we have to do.

We view it along the lines of, if I were a better, wife, mother, employee, business owner, consultant… The list goes on and on. If I were a better — I would be doing this thing. Clearly, I’m supposed to do it, so I should.

It may have no relevance, as you were saying, to what would be good, profitable, smart, in my best interest, and authentic for me.

I love what you said: authentic. We wear it as a hat, as if it is reality, one and done, and that’s it. It’s one way it could go, but very well may not go.

Having that open-handed versus “I should do it,” it’s very white knuckle. I’ll say that to my clients: “Are you saying, ‘I’ve got to do this,’ or can we open it up and say, is that profitable? Is that best for me?”

With clients too, it’s helpful to have that vision. If we’re clear on your vision and where we’re going, we can look and say, “Is this actually moving you forward towards that, or is it something you think you should do for some reason?”

Sometimes it’s even helpful to say, “If that didn’t exist tomorrow, what would you do?” That question can open up your mind to how things change very rapidly.

I love that. If we realize we have those feelings of “should” or something didn’t go the way we expected, and we have some residual emotions of sadness or grief that could be processed around that, what are the places for us to look to start moving through that?

One of the tools I like to use with clients is the Grief Recovery Handbook. It’s been an interesting tool for me. It allows me to close the loop on whatever I’m grieving.

I’ll share a personal story, my mom passed away when I was in my early twenties. I was young. Most people in my life hadn’t lost a grandparent, let alone a parent.

There were people who were much older than me because they had been living life and had experienced that. At the time, no one my age really knew what to say or do. There were the normal feelings of needing to get over it and keep moving because life doesn’t stop. Of course you feel sad, but you keep going.

It wasn’t until much later when I started looking at the process, that I realized there’s no actual timeline. What I particularly like with the Grief Recovery Handbook is it allows you to have all of the emotions.

My mom was ill. It wasn’t a situation where I could direct my anger at something or someone. Someone kind of brought up to me, “Well, are you angry? My response was, “Well, I can’t be angry about it. It wasn’t our choice.”

The grief process allowed me to have all the emotions. Sometimes for clients and humans, there are certain things we cut ourselves off on. We say to ourselves, “I have to move on. I have to feel sad for a certain amount of time, and then that’s it. I can’t feel certain ways.”

I really like the Grief Recovery Handbook because it closes the loop on anything and everything you might be feeling about a situation. It’s when we don’t allow ourselves to feel all the things that grief goes unresolved, even though we thought it was addressed.

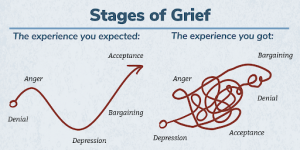

I love that. When I was doing research for our conversation today… We’ve heard of the five stages of grief. We think we’re supposed to move through them in sequential order. The experience you got shows that we don’t, we move back and forth and around in circles. We go over to acceptance and then back to anger. That’s how it goes.

You may never hit bargaining, for example, or you might never hit denial based on how you’re processing at the time. All of those loops and whirls, it’s not linear. Another important thing is giving yourself grace if you need to go back, because you’re not going back. You’re simply on the journey.

With anything in our type of work, sometimes I’ll say to my coach or therapist, “Haven’t we talked about this already?” As you get deeper, it comes back up.

Maybe when it first came up, it was a 10, now it’s a 7, and it will be a 3. It changes. The important thing is to not be upset about the fact something’s being addressed again, because as you clean things out, clear your mind, and heal, different parts of it appear. It has to be okay to deal with each part when it comes. You probably couldn’t have dealt with that version of it, let’s say six months ago or three months ago when the first part of it came up.

I love that way of thinking about it, we’re moving through stages. It’s sort of like an onion, there are different layers to it. The fact that it keeps coming up isn’t a problem. It’s just a matter of, “Now I get to deal with this layer of this thing that happened, or this situation in which I found myself.”

Sometimes something will trigger it. You’ll have a moment of, “Ooh, I’m feeling a little weird about this. Oh, you know what? That reminds me of this. Now I’ll deal with this feeling.”

The biggest thing, also, is taking ourselves off that timeline. That beautiful, lovely, straight arrow is not how life or healing works. It’s not how grief works. Giving ourselves the freedom to experience what we’re experiencing in the moment and address it in the moment is key.

I have a mentor who used to talk about how, in her mind, we are all walking around in one half of a Velcro soup. If you think about Velcro, it’s loops and hooks. We are all walking around in a loop suit.

Occasionally we keep getting hooked by that same thing and thinking, “Oh man, I thought I dealt with the fact that my grandfather was a jerk. Now here I am again dealing with the fact that my grandfather was a jerk.” It’s one of those things that keeps coming around, because we’re in a human loop suit.

That’s a great analogy.

There are things we can address now, we start off, we have a hammer and we’re hitting a nail. Later, we might be chiseling a little piece of dirt out of this beautiful sculpture with a little brush. That little artifact hammer you might be using is different.

It’s okay to say, “I couldn’t have seen that little piece if I didn’t use the hammer before.” The way it then occurs to us is a lot less painful. We get to say, “Okay, this is a little thing, and I don’t want the pebble in my shoe, even the grain of sand, because I will feel it, but it’s not a boulder.” It makes it easier to deal with it.

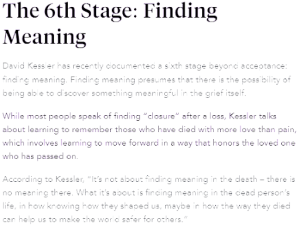

Absolutely. As I was doing research for today, one of the things I came across was the idea of a sixth stage of grief. It’s about finding meaning in whatever it is we’re grieving.

We could be grieving the loss of a loved one, or the loss of a situation, or a situation that was familiar. Maybe it wasn’t that great, but we knew how to function.

I worked for a Fortune 200 company. There were things about it that were awesome and there were a lot of things that were bad. When I left, I realized, “I have grief in the loss of this.” Even though in many ways it was a poor fit for me. I knew how to do it. I knew I was comfortable.

It goes back to, we’re always seeking safety, dignity, and belonging. I knew where I belonged, I felt safe there. I was respected, and then I lost all those things.

Comfort will keep us in place for a very long time. When you get laid off, for example, it’s hard to find meaning in that and think to yourself, “It’s a positive.” We can say, “Okay, this happened, now what do I want to do with it?”

That’s where having all the emotions comes into play. The loss of a parent you had a horrible relationship with or who is absentee, can be a hard thing to process because we can judge ourselves. We think, “I should feel sad, I don’t feel sad, or I’m glad they’re gone and shoot, I don’t want to feel that. I shouldn’t feel that way.”

The response is, let’s have the feelings as they are, say all the things, and not judge the process or how we’re feeling. It’s very easy to shame out around what or how you’re feeling.

When we find ourselves shaming out, and I love that phrase, how can we pull ourselves back? What ideas do you have around how we can get re-grounded in what truly is?

I’ll often use the Byron Katie framework of, “Is it true?” Let’s say a parent died and there was a negative relationship. You’ll think to yourself, “Well, I shouldn’t feel bad. I shouldn’t feel relieved that they’re gone.” Well, is that true? You do feel that way. It’s not about should or shouldn’t. That is how you feel. Let’s talk through why and how you feel that way.

That’s why, for me, I always let my clients know I work with a coach and a therapist. I encourage them to do the same. We need other people to help us walk through grief.

That’s where something like the Grief Recovery Handbook or going through that process comes into place. You can have all the feelings, you can talk about the things you want to acknowledge for yourself, the things you liked about the person, because there were probably one or two things you remember that you want to talk about and the things you’re not happy with.

Being able to say all the things helps us from going down a rabbit hole. It’s about reframing the question of whether you should or shouldn’t feel that way. It’s simply how you feel. You need to acknowledge that and not put any judgment around it.

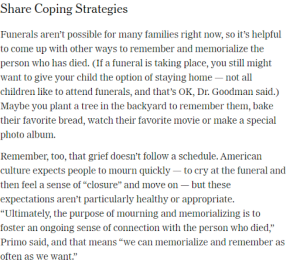

I love that. I came across this New York Times piece, and I loved this beginning about coping strategies. It says at the beginning of the second paragraph, grief does not follow a schedule and American culture expects people to mourn quickly.

We’re expected to cry at the funeral, and then have a sense of closure and move on. That’s not how many of us… even if what we’re dealing with is sadness and not grief, we don’t move through it that way.

The Jewish culture has some wonderful traditions around grieving. There’s a culture, I think it’s an African culture, where people who are mourning the loss of a loved one wear a band on their arm for a year. The expectation is, it’s going to take you at least a year. You want to have something public so people know, “I get to be a little extra kind to this person because they’re going through a grieving process.”

To me, it’s like waves.

The ocean is one of my grounding places, and part of what I love about the ocean is the movement, the repetition, and the fact that it’s never the same. Waves come in sets. Sometimes they come in sets of one and sometimes in sets of four. There’s an unpredictability in the regularity. I love bringing that idea, as you just did, to the concept of grief.

For me, there have been years where a birthday or a specific holiday doesn’t trigger any specific emotions, but seeing a flower at the store on a random Tuesday can. You never know how it will come or to what extent. Sometimes depending on other things, it might hit me extremely hard.

Other times it’s just a moment, a reminder, and all of those are okay. To your point too, and that article said it beautifully, the hard line of grief, the newness that happens right away gets easier and subsides.

I don’t know that, depending on what the loss is in certain instances, it ever really goes away, it simply changes. That’s the other piece I think we get wrong. We think it’s going to have an endpoint. It will feel different, but depending on the loss, you’re not letting go of the person, the memories, the relationship, and the things that molded you about the time you had together.

I have a close friend who passed away. We’re coming up on the one-year anniversary from cancer. I had the thought the other day, “Oh, I need to call Kirsten.” I can’t call Kirsten. She’s not here anymore.

I love this concept, it’s been coming up a lot around work people are doing with diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging, especially with the belonging piece, is the idea that everyone’s life is a movie in progress. Where I come into… so you and I connected maybe six months ago now.

It might have been a year at this point, I lose track, Janine.

Time is very funny these days. So six months to a year ago, and now something will happen and you will pop into my brain. Things happen in life, people come and go, and circumstances change.

One of our collective opportunities is to remember, where we’re coming in on anybody else’s movie is partway through. We don’t know all of the things that have happened beforehand.

If you and I are in Austin together, which would be awesome, and we’re in the grocery store and suddenly you tear up over a can of tomatoes, it’s not that you suddenly had a stroke and lost your mind. That can of tomatoes is probably connected to something I don’t know about.

Having that patience and compassion, and knowing I came into your story 30 years after it started… If we can all have that level of connection and compassion for each other, even with not knowing the background of anybody else’s story, it feels like it would be easier for us to manage our feelings and our grief.

There’s a level of empathy and curiosity we don’t always come at others with because we’re the star in our own movie. We’re thinking about the way everything is coming toward us, versus looking at that person or that moment in its own individual state. We don’t always ask, “What’s happening here now?” With the can of tomatoes, it could be, “Oh, Alyssa’s Italian. She used to make sauce with her mom. It reminded her of that.”

The key is getting curious, being open, and learning not to be afraid of the uncomfortable situations or the emotions of somebody else. Those situations can make many of us feel very uncomfortable. Our response is, “I don’t know what’s going on right now, but this person’s crying, what’s happening?”

The important thing is to keep the curiosity. There’s also the other thing that’s very uncomfortable, which is to hold space and keep the silence.

The opportunity to hold space for another person is a wonderful thing and something we often bulldoze over. Last night, my husband and I were having a conversation and he was having a number of feelings about something. It did not make sense to me why he was having those feelings.

I was trying to help him reframe the story he was creating because all the feelings he was experiencing were negative. I said, “Well, what if you could change the story so that…?” That wasn’t what he needed. Eventually, he was able to say, “I just need you to say I’m sorry.” I then understood and said, “I’m sorry. I did such a bad job at that, so tell me again.” We got to have a little do-over. What he needed was compassion in that moment for the feelings he was feeling.

Exactly, we think we need to be able to understand the problem to be there. We think we need to be able to relate, to understand exactly what we’re talking about to be with the person fully in the moment. We have to remind ourselves, we don’t need to understand, we just have to be there.

One of the cool things about coaching is being able to hold that space and saying, “This is a safe space to say the things you maybe can’t say anywhere else and we’ll feel the feelings.” In those conversations, you can see sometimes when somebody has a shift and you can ask what’s going on. Then let them articulate it, or not.

We are in this business time in the 21st century where managers are expected to be coaches. People don’t want a boss, they want to coach. Helping to create space for people… I was working with a client the other day who manages a large law firm, and she was saying, “It just takes so much time, it’s so frustrating.” I was holding space for her to have her feelings around that.

I said, “I get it. I get that it does take time.” It was way easier when managers could say, “I don’t care about you. Just produce the work that I need done and then go home.”

That is no longer the nature of work. When we show up that way, we lose our people. We are in a time when the war for talent is real. Finding the right people, getting them onboarded, and keeping them around is the name of the game for most organizations.

It takes a lot of time, and sometimes it sucks having to really care about all of your employees and hold that space for them. We get to grieve that. We get to grieve that it is no longer the way it used to be. I get it. That stinks and here’s what it is. From there, how do we move into that space with power and compassion for ourselves and ultimately for our people?

For me, being in the corporate space for, gosh, 20 years, even when I was first in it, it was not a space for compassion. Whatever was going on at home, you kept that to yourself and you put on your game face at work.

I have appreciated being in corporate while that shifted and seeing it shift because there’s an authenticity you cannot bring if you’re keeping a very large part of yourself out of the workplace.

Being able to come in the throes of life, which happens to all of us, and being able to have that understanding too, is really helpful. Otherwise, you’re getting some version of the person, but you’re probably not getting their best. Also, you don’t even have the understanding as to why you’re not getting their best self, in a certain moment if something’s happening in their life.

What we as organizational leaders need is the best from our people. Whether those people are us or the people who are working with and for us. Creating space for people to be fully themselves is critical.

I would agree.

Alyssa, this has been a delight. Thank you so much for your time, your wisdom, your generosity, and your insights about grief and the opportunities for us to move through it more fully. I really appreciate you being here.

Thank you, Janine. It was a pleasure. I love talking with you, so I’m glad I could share. Thanks for having me.

Back at you, babe. I am Janine Hamner Holman, and this has been The Cost of Not Paying Attention. Remember, great leaders make great teams. Until next time.

Important Links

About Alyssa Gioscia

Alyssa Gioscia is an Executive Coach, Organizational Development Specialist, and Leadership Trainer with a successful track record of enhancing organizational results by harnessing the talent of people, the pursuit of vision, and the focus of strategy.

With experience reaching audiences exceeding 750 team members, across 15 company offices, in 5 different companies, Alyssa has always remained committed to getting to the heart of people’s unique stories and partnering with them to produce powerful legacies – for themselves and the clients they serve.

Her ability to positively impact the health of a company, respective of revenue outcomes, risk mediation, and culture enhancement is a testament to her ability to successfully join human talent and strategic design for high-value organizational performance at scale. She is passionate about getting to the heart of people’s stories and partnering with them to produce powerful legacies.