Do you understand your instincts, and how they affect your work? Does your organization work with everyone to find “conative” solutions? In this episode, Janine Hamner Holman sits down with Beth Banks Cohn, an organizational consultant and thought leader who helps organizations learn about implementing change.

GUEST: Beth Banks Cohn | LinkedIn

HOST: Janine Hamner Holman | [email protected] | LinkedIn, Facebook, Instagram

What am I paying attention to right now? I recently had the opportunity to be up in Paso Robles, which is the Southern California Wine District. It’s like the Napa of Southern California. It’s especially known for its red wines, of which I am a fan! I was up there on Tuesday (Valentine’s Day) because I was speaking with a group of about 100 HR leaders from what’s called the Central Coast. I did a keynote talk and engaged with them, which was super fun.

One of the things we talked about is what has happened over the last two decades in the domain of leadership. We spoke about the difference between what leaders needed to be in the 20th century and what leaders need to be in the 21st century.

We talked about the fact that it feels like the pace of change is moving faster than ever before. We realized that this ubiquitous piece of technology that we all have, whether it’s our iPhone or our Android, didn’t exist until 2007! It’s a thing we all have attached to ourselves, which I believe, in part, has accelerated the pace of change.

That brings me to our guest for today, Beth Banks Cohn. Beth is an accomplished organizational consultant and thought leader with more than 25 years in the pharma, biotech, IT, high-tech, and manufacturing industries. She’s regarded by many as an authority on culture and leadership change, and is a sought-after speaker on organizational change. She and I have that in common.

She began her career at Johnson & Johnson and, over her 16-year tenure, she held various positions of progressive seniority at Johnson & Johnson. She holds a Ph.D. in human and organizational systems from Field and Graduate University and has authored numerous blog posts and several books.

Her most recent publication is an essay in The Secret Sauce for Leading Transformational Change book. How juicy does that sound? Welcome to the show, Beth Banks Cohn.

Thank you so much, Janine. So wonderful to be here.

I’m going to begin the way I often begin, which is: what is something you have noticed, Beth, that we are not paying enough attention to, and what is the cost of that inattention?

For me, having worked in change for decades, what we’re really not paying attention to is the three parts of the mind we need to focus on. When we’re dealing with change, we focus on how we feel about it, and we sometimes pay lip service to the cognitive, to what we want to tell people about it.

We definitely don’t pay attention to the “conative” (more on this word and concept later!) or the “doing” part of the mind, which is where our instincts and natural talents sit. Often that’s because it’s more personal, and companies just want to implement change on a macro level. The truth is, change gets implemented on a micro level, person by person. We’re definitely not paying attention to that.

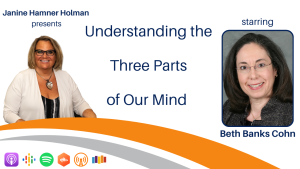

I love that distinction. In preparing for this episode, I found this graph. What I love about this is that in my experience, sometimes what happens is we get stuck in this “exploration reorientation” part. The change is coming, we know what the change is, we have shock, denial, anger, blame, anxiety, and uncertainty.

Then we have confusion, resignation, impatience, and innovation… maybe. It’s hard sometimes to get fully up the next hill to acceptance, commitment, energy, and willingness. I would love your take on this “U” we get stuck in sometimes in the change cycle.

This is a great picture for looking at change. It’s not so much we get stuck, it’s that we haven’t received the commitment that’s needed to get further. Companies want everyone to feel good about the change. The truth is, employees need to believe in the change. They need to believe in it because you’re asking them to sacrifice something: energy, time, their job, or their career. There’s always a sacrifice for employees.

We don’t get people to that belief level when it comes to change. That’s one thing. That’s why we get stuck.

Another reason is that we don’t cognitively give people enough credit for being able to understand and get to the evaluation level.

Sometimes companies will say to me, “Well, we told them that we were doing it.” My response is, “Yes, but you didn’t tell them why, or give them the whole picture. You gave them the end result.” There are plenty of people out there who need to know, “You decided to do this, but you didn’t decide to do that. Why didn’t you decide to do that? Why is this the best decision for us right now? What are we going to do if it’s not working?”

That’s all a cognitive thing, and we don’t do that. So people aren’t fully on board.

The last thing is, often we change people’s jobs in such a fundamental way that from a “conative” or “doing” perspective, people have to be willing to direct personal time and energy. Sometimes they don’t have the right energy to do what you’re asking them to do because that’s not where their mental energy sits.

We all have a limited amount of mental energy and it’s divided into different things. Sometimes you’re asking somebody to gather information when they’ve never had to do it before, and it’s not their talent.

We need to be thinking about all of those things. There are a lot of reasons why we don’t get to “new beginnings.”

I love this idea that we need to give people more information. It’s so fascinating to me how hung up leaders often get about giving out the information and thought process that got them to the place where they are now. Sometimes we are really reticent to give up those details.

I’m curious, Beth, in your experience at helping people through this, do you have any insights or thoughts about why we get so stingy with information? Why we don’t want to bring people into that conversation about why we didn’t choose this and why we chose that instead?

From my experience, it’s been really simple. They’re done with the conversation. It wasn’t such a great conversation, maybe it was painful. They had it a while ago. They’ve already talked it out. They don’t want to talk it out again.

They don’t want to go through the comments people are going to have. “Well, did you think about this? Did you think about that?” Because they think they’ve thought of everything. They just don’t want to have that conversation again. They don’t want to open themselves up to having that conversation.

I get it, but it doesn’t work.

It really is backfiring. We understand this from the Kolbe Index: there are different people with different needs for information. You have to give them some information that allows them to understand your decision. You can’t just say, “This is the decision.” You really do have to go into more detail.

When you do, people are going to ask more detailed questions. Leaders, they’re done. They just want to move on. When I speak with leaders about change, I say, “You’ve gone through the stages: denial, resistance, and acceptance. Now you’re in commitment. Like you’re here.”

Everyone else is in denial and you need to bring them to where you are. They’re going through the curve. If you are here and everybody else is in a different place, you need to bring them along. You can’t do it by saying, “Shut up and get back to work.”

It’s so brilliant. I love the connections between my first thought about 21st-century leadership and this idea of bringing people along. Being more inclusive and less micromanaging. Less command and control and more engaging, flexible coaching with people instead of dictating to people. These are the key tenets of what it takes to be a great leader today. These are also the things that make a great change leader.

You’re spot on about, if we’ve gone through a difficult process to get from there to here, by the time we get ready to announce the decision, we don’t want to go back to Step A. The cost of not doing that is people get disengaged and stuck in “the U.” They don’t understand, and then they don’t buy in, and they get disruptive.

In your experience in leading people through change effectively, what are the costs you’ve experienced of people not bringing others along with them? What is the opportunity when leaders do take the time to go through, “I went through all that pain before; I don’t want to do it again, but I have to. There’s going to be some good juicy stuff at the end of having gone through it.”

What’s the payoff?

The cost is that you don’t get your return, from a business perspective. You might have sold this change as a way to get a 10% or 20% boost, but you’re not going to get it. You’re going to have to be satisfied with getting less than what you anticipated.

You went through this painful thing to get to where you want to be. Now you’ve announced it, but you’re not going to be able to implement it fully because you’re not bringing your people along with you.

You can implement it, but you’re not going to get the adoption you need for it to make a difference. Leaders will say, “Okay, well, we’re just going to implement it and then we’ll work on it.” Instead of focusing on wanting everyone on board because they need immediate acceptance.

What they should say is, “We’re going to go through the conversations in order to make that happen. It will slow us down for a month, but the uptake will be so much faster when we actually make it happen.” That’s being willing to go slow to go fast in the end. When you do that, then you get your return. Because you’ve based your return on something.

Maybe you’re saying, “Well, okay, maybe only half of the people are going to be interested in this, or half of the people are going to follow what we’re trying to do.” That’s fine. But if you’re willing to take less, what are you doing it for in the first place?

Why are you going through all of this if you’re going to get half the potential results?

I’ve worked with teams where they follow the process that I use, and they do the things they need to do all along the way, taking into account the three parts of the mind. Then they get way more than they bargained for because they’re doing it efficiently.

Everybody’s doing it better. Productivity doesn’t fall, when often productivity plummets when you implement change. It doesn’t have to. I’ve worked with teams where productivity doesn’t fall because you’ve done all the things you need to do in order to make that change happen.

Companies get caught up in, “I don’t want to have the conversation again, and I don’t want to have to learn something new that might change the outcome. I have a really good case, we’ve talked about it, and we’ve debated it.”

Then someone a few levels below you says, “But what about this?”

It can change everything. As a leader, you have to be willing to work with change to be a great leader. The truth is, being a great leader is synonymous with being a change leader. To me, if you’re a great leader, you’re a change leader. If you’re not a great leader, that extends to a lot of departments… including change.

The downside is you don’t get what you’re looking for. The upside is you can get more than what you’re looking for. I once worked with a team that had this increase in business that they never anticipated, because we went back and did exactly what they didn’t want to do. We did a pilot and then took the feedback and changed the process. When they implemented the change, there was 100% adoption.

Then it was kick a**!!

They were wildly successful!

Why wouldn’t you want to do that? I get why they don’t want to do it. I feel their pain. At the end of the day though, you need to do what’s best for your company, not what’s best in the short term. You want to do this thing because you want to be seen as doing it, but it needs to be about results. What are you accountable for? Are you accountable for flipping the switch or are you accountable for the results that come after?

I came out of the IT world and it used to be that flipping the switch was a success. There were a lot of “flip switches,” but not much success.

That’s changed.

My question is, do you want to flip the switch or actually make a change that’s significant, sustainable, and will make a difference for your business? Why else would you go through change unless you want to make more money or make a bigger impact? Why would you sell yourself short for expedience because you’re done with the conversation? That’s a little self-centered.

We all have that. The “I’m done with this conversation. I don’t want to do this anymore.” We all have the “I have cogitated over this. I’ve brainstormed with other people. We found a solution that I feel good about. I think we need to just implement it. I do not want some yahoo three rungs down coming up with new questions.”

As you said, when we are willing to go slow to then be able to go fast, we may come up with a better way to do something. We’re going to get the buy-in we need to have the change be effective and sustainable. It’s one of the things when we think about 20th-century leadership. In the 20th century, we had all of these people… Lee Iacocca, Jack Welch and people who became synonymous with their brand.

It was a style of leadership that was very much about the leader and not about the organization, and definitely not about the people in the organization. Then you think about where we’ve come to now, where it is about the people and the experience they’re having, so we get the buy-in, the processes in place, and then the productivity. Then we are profitable, we’re producing the widgets or the thought leadership, in order to be successful as an organization.

All change involves some level of difficulty. When we can look at where we’ve been and where we want to go, it gives us that opportunity to see, “Okay, there are some things about it that are hard, but this is what’s going to be successful. This is what’s going to create people who are thriving,” which then leads to thriving organizations.

There’s no question about that. Sometimes leaders also forget that they’re introducing a change into a functioning environment. Sometimes they’re somewhat unaware, which always surprises me, but it never should, about the other changes that are going on.

You really have to think, “Well, what else is going on? What else have I done that has affected these groups where I’m now introducing even more change?”

People get change fatigue. Since the pandemic, it’s rampant.

We all have a level of change fatigue and burnout. There’s been so much uncertainty we’re all swimming in all the time. Then you layer on the world news and mass shootings and all of the things that are happening in the world. It’s not surprising that in 2020, 2021, and 2022, this topic around burnout has expanded, with new books coming out every week. The WHO classified burnout as an organizational problem. It’s no longer “I am burned out.” It’s, “This organization is causing me to be burned out.”

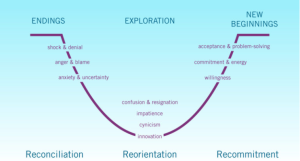

How do we address the organizational issue, which I think is part of where your brilliance comes in? I want to talk about this idea of the three parts of the mind. You’ve touched on this a bit, and I would love for you to dig into the cognitive and the affective, and then this word many people don’t know: “conative.”

We’ve known that we have three parts of the mind since Aristotle wrote about it. It didn’t get picked up as time went on, but plenty of people wrote about it. Later on in the mainstream, psychology dropped the idea, mostly because they couldn’t figure out how to measure it.

You can measure IQ and you can measure feelings, but it was difficult to measure instinct. How do you measure instinct? Psychologists didn’t talk about it a lot, but around 40 years ago Kathy Kolbe was interested in things you couldn’t explain through the cognitive or affective parts of the mind.

She went back and did research. She found out that there was this third part of the mind, and she set out to create an instrument that measured it. She’s been quite successful. It’s called the Kolbe Index. These three parts of the mind have to work together. They’re not separate, but you have to know and give credit to each of them.

We have the affective, our “feeling” part of the mind. It’s where our motivation, preferences, values, and beliefs are. It’s important to pay attention to that, and not just at an individual level, but also at an organizational level. Most instruments we use today, DISC, Myers-Briggs, and StrengthsFinder, they’re all measuring this affective part of the mind. That’s fine; it’s important.

Then we have the cognitive or “thinking” part of the mind. That part is where our IQ, skills, knowledge, and experience are. We have a domino effect in the mind that gets kicked off by these parts. In the affective, if I’m motivated or I’m thinking about something I have feelings about, my cognition basically helps me frame it.

It says, “Oh, I know about this. I have knowledge about this, I’ve been educated about this.”

Then there’s this third part of the mind, the “conative” or “doing” part of the mind. This is where our instincts sit, our drive, things that we have to do that we don’t even think about.

We just have to do them, it’s our innate talent and mental energy.

Mental energy is something that, from a pandemic perspective, we should definitely have been paying more attention to. People have a limited amount of mental energy, and it can be replenished, but you have to take time off in order to do that.

When people moved into their homes and they were working all the time, they weren’t replenishing this mental energy. It’s one of the things that led people to get burned out. Burnout happens because we’re constantly trying to work on empty.

This “conative” part of the mind is where our instincts sit, things we do when we are motivated to solve a problem.

Motivation is affect. When we’re motivated to solve a problem, our instincts kick in and we have a way of doing it that’s our unique natural way. It’s something we’re born with. It’s not even something that we develop over time.

Then society “helps us” decide if we’re going to pay attention to it or not.

For example, one of the ways people instinctively take action is by gathering and sharing information. If you instinctively do that, and your instinct is to gather lots of information, you are perfect for the American School System because that’s what it values. People in that system have to be very organized and systematic.

Then there’s another type of “conative thinking”. When you’re faced with a problem, if your instinct is to start to go in there, find options, brainstorm, try things out, and see what works and what doesn’t work, then you’re going to struggle in a world that requires you to be a fact-finder.

You are not ever going to be gathering enough information for the school system. When you get out into the world and you’re free to be yourself, then your instincts get to shine. In companies, we hire people and they have instincts, and if the instincts don’t fit exactly the way we want them to, they spend their entire careers trying to be something that they’re not.

When somebody says to me, “Well, your desk should be neater.” It used to come up on my performance appraisals. I would respond, “I’m sorry, was that in my goals and I don’t remember? I exceeded expectations, and we’re talking about my desk?” Because it’s not my instinct.

Companies get caught up in the wrong stuff. People go into jobs that they aren’t instinctively suited for… but they chose those jobs because it’s what they believed they were supposed to do.

People who become lawyers and then end up doing something else are perfect examples. They thought they wanted to be a lawyer.

They certainly had the fact finder to get through it, but then realized it wasn’t for them. Some people stay and they’re miserable their whole lives. In your case, Janine, you got out and you do something for which you’re more suited.

We lose touch with this “conative” part of our mind because society tells us we have to be a certain way in order to succeed, and we work to make that happen. For some people, it’s easy because it’s part of who they are. For some people, it’s a slog fest.

This just happened with one of my grandsons. He’s an “initiating quick-start,” and he thought he was supposed to go to college. It turned out that he decided after a semester, no, that’s not what he wanted to do. He wants to do something else. What he’s doing is more suited to him, but society instills in us the value of “You must go to college.”

He’s going to do really well in life because he’s going to be working with his instincts, and he’s going to be the best person he can be, working in a job for which he’s suited… and he’s going to make just as much money. That’s what we want, but we’re not paying attention to this dynamic neither as a society nor within companies.

We don’t pay attention to these things, and it makes a difference.

We talk about trying to get people to not “have burnout.” When you make someone work against their grain all the time, and you say to them, “I want you to stop experimenting. I need you to just gather the information, pay attention, read this spreadsheet, and tell me what the spreadsheet says.”

That’s not their instinct! They can do it, but the energy it’s going to take from them is not the energy that it would take from me as a “fact-finder.”

This is fascinating!

To our readers, if you’re interested in finding out more about the Kolbe Index you can go to www.Kolbe.com. You can also reach out to Beth Banks Cohn. She’s the only one on LinkedIn.

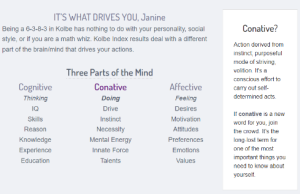

I took the Kolbe test last night because I thought it certainly might come up today, and it might be interesting. It cracked me up in the “don’t” category. It showed me where I should not be spending my time:

- Do not demonstrate the use of mechanical stuff.

- Do not take responsibility for maintaining equipment.

- Do not take apart small appliances.

- Do not fix broken parts.

- Do not build many physical models.

I hate all that stuff! It’s the reason that when I get a new appliance, I take it out of the box, and I start playing with it. I do not read the instructions. Instructions make me crazy. My dad is the exact same way. I always thought I learned it from my dad. With this idea of “conative thinking,” however, this is just an instinctual thing in me.

Exactly. According to Kathy Kolbe, there are four action modes. One of them is the “implementer.” That’s what you just showed. “Implementer” is how we physically handle space and tangibles. We all do it in some way.

You and I both “envision.” We can picture somebody fixing it, but we ourselves are not going to fix it. I always say, I have enough mental energy to take it apart, but I do not have enough mental energy to put it back together. You have a set amount of mental energy. My smallest amount of mental energy gets put into “implementer,” physically handling space, and intangibles. I always say it’s what a checkbook is for. I call somebody. I’m not fixing it. And you don’t want me to.

It’s what my best friend calls a VGUM: a very good use of money. If I need to fix my car, I don’t know what the problem is. It has a light or a weird sound, and I am not going to figure out anything to do about it, other than take it to someone.

It’s like changing oil. When I bought my first car, somebody said to me, “Oh, I can teach you how to change your oil.”

No, thank you.

I’m taking it to the dealer, and it’s going to cost money. I’d say to that, money well spent.

That’s right. Because I’ll end up with a screw and other leftover pieces. I don’t know where those parts go.

What’s interesting about the Kolbe index is that it isn’t mainstream. It answers the unanswerable questions. People will ask, “Why am I like this? When we go into a room to brainstorm, why am I always the one that’s very quiet? Why am I the person who can’t work on multiple things? I can only work on one thing at a time.”

People think it’s a character flaw. This is the thing that kills me. It’s not a character flaw! That’s who you are. Let’s figure out a way to make that work for you. It won’t change. You can learn how to work on more than one thing at a time, but it’s always going to feel uncomfortable, and you’re never going to be efficient.

Why don’t you just work on one thing at a time, finish it, and move on to the next thing? I mean, that’s not me. I don’t do that. You, Janine, don’t do that either.

People do think that some of these instinctive things are character flaws, and it breaks my heart because they’re going through life thinking that they’re deficient in some way.

They’re not. That’s what I love about the Kolbe Index. It helps you feel whole.

From a change perspective, it gives you another insight into why a change is working for you or not. Because it could be there’s something about the change you can’t believe in, so you can’t, from an affective perspective, sacrifice what you need to in order to support the change. Maybe it’s that cognitive … “I’ve researched this and I think this is the wrong way to go.”

There’s a way to deal with that because there are plenty of people who think it’s the wrong way to go, but you can always treat them with respect and say, “We’re going to try it this way. If it doesn’t work, we’ll try it your way.”

The “conative” is, “This job has now become something I can’t manage. I go home every day, I’m exhausted and don’t understand why it takes me forever to do this PowerPoint.” Those are symptoms for things that are out of whack from a “conative perspective” that you have to pay attention to because how you’re working is not working for you.

When people get that insight, it takes a load off their minds and allows them to be better at change. Once you know who you are and what’s going to work for you, you can figure out how to make a change work for you. We often don’t do that step. We put the change on people instead of saying to them, “This is the change. Let’s figure out how it’s going to work for you in the best way possible.” We definitely don’t pay attention to that.

I love that. How can we make this work for you? That is the destination that so many of us, especially consultants, are helping organizations find. “How can we make your organization, change, or system great for your people? How can we align the organization with your mission, vision, and values so it resonates with your teams, so they feel connected to that and want to come to work, do a great job, and serve your customers well?”

I love that. Thank you for bringing that into the conversation.

Absolutely. I love what you said. It comes down to: people do get up in the morning and say, “I want to do a great job today.” Then they get to work and sometimes they just can’t. That’s why our goal is to get them to a different spot because you can get the best out of each and every one of your people. You just have to pay attention.

That’s why the show is called The Cost of Not Paying Attention, so we can shine a light on those places and hopefully help everyone pay a little bit more attention to some of the critical things.

Beth, thank you so much for being here with us today and sharing all of your wisdom about the Kolbe Index and “conation,” which I had never heard of before. I am looking forward to continuing this conversation with you for many years to come.

Oh, thank you. Me too. It’s been an honor today, Janine; thanks for inviting me.

I am Janine Hamner Holman, and this has been The Cost of Not Paying Attention. Remember, great leaders make great teams. Until next time.

Important Links

The Secret Sauce for Leading Transformational Change

About Beth Banks Cohn

Beth Banks Cohn is an accomplished organizational consultant and thought leader with more than 25 years in the pharma, biotech, IT, high-tech, and manufacturing industries. She’s regarded by many as the authority on culture and leadership change, and is a sought-after speaker on organizational change.

She began her career at Johnson & Johnson and over her 16-year tenure, she has held various positions of progressive seniority at Johnson & Johnson. She holds a Ph.D. in human and organizational systems from Field and Graduate University and has authored numerous blog posts and several books.

Her most recent publication is an essay in The Secret Sauce for Leading Transformational Change book.