Is love a part of your business strategy? What do you think of when you hear that question? Do you start to think about rom-com films? In this episode, Janine Hamner Holman sits down with Jeff Ma and Chris Pitre, two leaders in workplace culture and communication, to discuss the role love plays in business.

GUESTS: Jeff Ma | LinkedIn | Chris Pitre | LinkedIn

HOST: Janine Hamner Holman | [email protected] | LinkedIn, Facebook, Instagram

What am I paying attention to today? I saw an article in the Harvard Business Review, where I’ve recently become a member of their advisory board, that’s unbelievably thrilling to me. The article talks about how tension around working from home is escalating, mostly with employers wanting people back in the office and workers wanting to stay home.

This has been both the dynamic and the tension for some time. According to the article, it’s ramping up and it’s seeming like people are becoming more entrenched and having a harder time hearing another perspective.

You may think, as I did while reading this article, it feels as though this is incredibly endemic in our society today, with everything from the political stage to the writers and actors striking against the studios and streaming companies and AI on the other side to these challenges that we’re having about working from home, returning to the office, or a hybrid approach. It’s seemingly having to do with our ideas about productivity, which is fascinating because both sides of the argument say productivity is better, with organizational culture and with ideas about the individual versus the collective.

I was approached earlier this week by a large organization in DC in need of help with this very issue. Their question is, how do we create, and then maintain psychological safety when we’re working on being a hybrid organization and some are still wanting it to be all one way or the other? We live in interesting times, which brings me right to our guests for today. I’m so excited.

Chris Petre is the Vice President at Culture Plus and Soft Way. He’s the co-creator and facilitator of Seneca Leaders. He’s the co-host of the Love As a Business Strategy podcast and one of the Wall Street Journal bestselling authors of Love As a Business Strategy. He manages the company culture and works to ensure all projects, interactions, and deliverables reflect the company’s human-first approach.

Jeff Ma is the director of product development at Culture Plus. He’s the co-creator of the Seneca suite of products and services. He’s the host of the Love As a Business Strategy podcast and one of the other Wall Street Journal bestselling authors of Love As a Business Strategy. I recently had the opportunity to be a guest with Jeff on the Love As a Business Strategy podcast. It’s great to see you again, Jeff, and welcome to the show to you both.

(Jeff) Thank you.

(Chris) Thank you for having us.

I’m thrilled to have this conversation. Jeff and I had a great time when I had an opportunity to be a guest on y’all’s podcast, and I’m excited you’re here with me. I’ve read your book, and my copy has many underlinings, circles, and stars.

I want to start right where your intros left off: Love as a business strategy. I know you guys are serious about this and I’m right there with you, but seriously, love as a business strategy? Talk with me about how you landed on this idea and the reception you’ve gotten from other business leaders with whom you’ve had an opportunity to connect about love as a business strategy.

(Jeff) It’s important to first clarify what we mean by love. Everyone’s drawing their own conclusions, and I’m going to steal this from Chris. He says this more often than I do, but I’m going to go ahead and steal it.

When we say love, we don’t mean romantic comedy love where your hot best friend is your soulmate, and you don’t find out until two hours into the movie. We don’t mean everyone’s holding hands, singing kumbaya, running through the fields, and there’s no running water, like Little House on the Prairie.

When we say love, we boil it down to putting people at the center of the decisions we make. That may be an oversimplification, but if you draw out and look into the behaviors we’re talking about, what we expect from each other, how we treat each other, how we trust each other, and the relationships we build in order to arrive at this, it’s centered in a place of love.

It’s that kind of love you can understand better if you think of tough love, the love for someone you truly care about. When you really love someone, you tell them what you know they need to hear and you don’t hold anything back, even if it’s a difficult conversation.

That’s the kind of love we’re talking about. I want to start there because we intentionally say love to get your attention, but now that you’re here, we want to boil it down. This is not lovey-dovey, it is real human love for each other.

(Chris) Regarding your question about how audiences receive this, especially in the executive suite, it runs the gamut, but it’s pretty polarized. You have people who immediately love it and they want all of it. Then you have people who are skeptical or resistant. Once they’re introduced or have a conversation, they typically see it’s what they naturally believe in or at one point in their lives believed in or were trained in as young kindergartners.

They tend to come around once they understand we’re not talking about being doormats. Oftentimes you’ll notice many executives tend to have a jaded view of everyone in the workplace.

We often get the response, “Well, what about the bad actors?” My response is, “Are you hiring bad actors? We need to have a different conversation if that’s where you go first when you hear this concept.” If you’re hiring so many bad people you’re worried about who’s going to be taking advantage of all the things you bring to the table, that’s a separate problem.

I’m going to pick up right there, because when I’m talking with organizations about organizational culture and development, invariably part of what comes up is, “But what about the problem children? What about the people who are not behaving well?”

We all have worked with and for some folks who were being naughty. How do you help them understand what the cost is of people being naughty in the workplace, and then help them move through those issues?

(Jeff) Before we dive into that piece, I want to divide it into the people we have the perception are bad actors and the people who truly are bad.

I’m not saying everyone is wholeheartedly perfect and good-willed all the time, but what we have seen consistently is that we as humans are skilled at filling in the blanks. What we perceive is rarely the whole story, but somehow it always feels like the whole story. We will receive bits of information and in the places where we don’t, we fill them in. That’s often with our own assumptions and biases. Everybody does it.

One of the things we first try to get people to understand is we’re all going to “misbehave.” Sometimes it’s intentional, sometimes it’s unintentional. As humans, you have to accept this actuality first. There’s this perception of thinking, “We want to build a workforce where our high-performing teams mean we never hurt each other’s feelings or get angry or frustrated with each other.”

That doesn’t work though, because conflict is healthy. Conflict is how we make progress. That’s why so much of our time is spent on finding ways to get people to have the relationships needed to reach not only not misbehaving with each other, but actually, forgiveness, which is a topic not brought up in that way in the workplace enough. When you think about it though, we can talk about all these other things all day.

We can talk about psychological safety, we can talk about all these things, but inevitably we’re going to fill in some blanks that have people at odds with each other.

You’re at a crossroads where you can choose to talk about it, open up that conversation, make it awkward, but come to a place where you can understand each other, agree to disagree, but also forgive each other. The other option is, you smile and nod, stick to the agenda, and work together for years and years, slowly building up resentment.

Unfortunately, the latter is a reality of what’s going on. Often when we talk about bad actors and underperformers, my first question is, “How well do you know that person and what is this based on?” More often than not, there are missing pieces to the story and we haven’t bothered to have the intentional relationship-building and connection to uncover where the source of the story is.

(Chris) In my experience and all the situations where we’ve been brought in to work with different companies and leadership teams, the bad actors typically have no idea they’re known as the bad actors. No one has ever given them feedback. They have no self-awareness.

As Jeff mentioned, because people have built these stories, people have also built up the resistance to go and give them said feedback about their behaviors. In corporate America, we love to give feedback about someone’s tactical executions, misspellings, wrong colors, logos being in the wrong place, and all that stuff.

We rarely want to prompt feedback around, “Hey, in our meeting you said this thing, and here’s what it made me feel. You asked this question and I know you might have wanted to get the information, but how you worded it made me feel X, Y, and Z, or I saw the look on this person’s face or the team’s face when you said X, Y, and Z, I don’t know if people received it the way you intended.”

That kind of conversation is rarely happening. We have this assumption, typically around the bad actors, that they know they’re misbehaving, they know and are intentionally causing these rifts inside of the team or organization. Many times, I’ll say nine out of ten, they have no idea people think they’re horrible coworkers.

It’s easy to write people off as bad actors rather than understanding what’s driving their behavior and giving them the chance to pivot. We go in and we believe everybody’s capable of change. They have to want it.

We don’t want to put an organization or business case in front of them and say “Change so we can make more money.” The case is sometimes, “Hey, I don’t know if you know this, but people don’t want to work with you.” Or “It’s difficult to get you to see different approaches or perspectives or to work alongside people you disagree with. I don’t think it’s because you’re intentionally trying to make it harder or you don’t want to try new things. There might be other things, and we don’t know how to help bridge those gaps or how to bridge you across to a better way of working.”

Having those hard conversations sometimes can be tricky, but if you’ve already written someone off or pre-judged the situation, it’s easy for bad actors to stay bad actors. It’s easy for hurt people to continue hurting people because no one has stopped and said, “This is probably not the best way to handle these situations.”

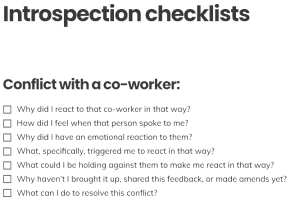

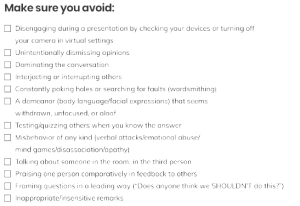

In order to say, “That’s not where you want to go, buddy.” You need a level of trust and communication. One of the things I think is so awesome about what you guys are creating is that you have so many resources online you’re just giving away to people. I pulled this off of https://www.loveasabusinessstrategy.com/.

There are so many resources out there and I want to applaud and admire you guys for creating and gifting it to us all. In order to have those conversations, you’ve got to have trust. You’ve got to have some level of Amy Edmondson’s psychological safety where you know you’re not going to get fired. How do you guys begin that process?

(Chris) When it comes to trust, it starts with getting to know people. In the situation to speak up, it’s not only about trust with the person across the table who might be having sort of those behavioral moments that aren’t good. It might have to be about trust outside the room to know you’re not getting fired for speaking up to the rainmaker or the highest performer who’s not the easiest to work with.

If it doesn’t go well, that trust tells you, you still have a place here to be safe. There might have to be trust in that way too, but I think it starts with the relationship. Do you know that person or your team well enough to understand how are they feeling? What are they going through? What’s their background? What’s their story? What did they come to be? What are their ambitions?

Oftentimes it becomes difficult for leaders to start with those questions because most leaders are all about productivity and efficiency. We don’t need to know that stuff because we are all here to do a job. We are all here to get the work done. We are all adults, we’re all making a paycheck, and we find those reasons to justify being transactional. We have to intentionally stop that behavior and train of thought.

The resources we created were shortcuts for leaders who have not been trained in those ways to start relationship-first, to see how they can easily get there. The results that happen faster and push you further are oftentimes not realized in many interactions in the workplace.

It starts with if people know each other. Even if I don’t know your intent, but I know you, your background, your story, what you’re about, what you’re interested in, and what your goals and ambitions are, I can use those things to inform how I give you that feedback.

If I know you are about making sure this project is on time and on budget, I know that’s a big goal for you because on the other side could be a promotion or opportunity. I don’t know if you realize in that meeting what you said might push the team into a bit of a swirl and you might have your timeline at risk. I want to bring that to your attention because I know that’s not what you want, but also what you want is being pushed further away from you.

Using those things to help teams see, “I know what I want to do and what I want to achieve, but my behaviors are getting in the way of the team realizing and supporting me in that outcome.”

(Jeff) The one thing I’ll add is, an easy way for me to help people understand trust better.. because trust is just this word you hear and you have a certain understanding of trust. We all understand trust, but the type of trust… an easy way I’ve found for people to understand is when I explain there’s trust and then there’s trust in others’ intent. Our intents are rarely exposed and obvious. No one can read your intentions.

There’s an element of building on what Chris said: When you get to know people, you can move closer to genuine trust and intent. If you ask anyone, “Hey, do you trust your team?” They’ll respond, “Yes, I’ve been working with them for years and I can count on them.”

However, there’s a different question. If you use this as an exercise and ask, “If one of my team members who I trust were to do something egregious which is clearly meant to cause harm, or by my perception meant to cause harm is your first step to respond with, ‘Oh my gosh, what kind of evil plot are they scheming?” Or is it instead, “They must have a good reason for having done that, and I want to understand why.” Those two are very different relationships, and they’re not far apart. All they take is a little more investment in each other.

It doesn’t mean you have to be best friends. The reality is that almost all of us show up to work with good intentions. We don’t wake up in the morning to come and cause someone else grief.

We all try to come in and create the best outcomes for ourselves and others. That means the majority of these issues are misunderstandings and places where we are not seeing each other’s intentions in the same way. If we can understand that piece, then we can come to the workplace with a different mindset of looking around us and evaluating what trust sits between us and other folks.

I don’t only mean, “If I ask them to do something, they’ll do it.” I mean, “If they really trigger me, where might they be coming from? Am I more curious or am I quick to anger?” That difference can tell you where trust is.

You said a word, mindset. In part, what you’re talking about is a combination of the assumption of positive intent and the mindset we come to things with, and the possibility of being curious even when somebody may have triggered you, hurt your feelings, made you mad, or disrespected you, one of those things which send us into an amygdala overdrive and we’re ready to fight, flight, and freeze.

Tell me more about that intersection for you guys. Then I want to go back to something Chris had alluded to around introspection. Let’s start with mindset and assumption of positive intent.

(Jeff) We have a framework, and the reason I’m bringing it up is that, as we went through this journey of our own, everything for us is based on our own practical learning. We’re not researchers and we’re not PhDs in psychology.

We are people who’ve been basically at the bottom, at the very lowest of lows. Then we learned through a lot of errors. Now, we share our story. We don’t come out claiming to have all the answers, but what we do know for ourselves, we’ve put into a framework. I’ll visually describe it a little bit. You can find it in our resources and it’s on a page in our book.

This is the framework we formed because, even as we’re talking now, we’re leading you down different paths of connection. That reminds me of psychological safety, and that means trust.

They’re all connected. There’s not one silver bullet. Our framework says a culture of love is made up of six pillars, and these six pillars together are synergistic but also necessary for each other. I mentioned forgiveness earlier, that’s one of the pillars.

You can’t address forgiveness alone though. You need trust, vulnerability, and things like that to bring it all to life. You also can’t address vulnerability alone. It does nothing on its own. You need to utilize other things like inclusion and empowerment to reach these kinds of goals. They’re all connected and we bound them all together.

Once we understand all six of these pillars form a culture of love, we have a foundational section that sits below all these pillars. We call it “behaviors” to simplify it, it’s how we treat each other.

The behaviors start with one simple box on the diagram, “mindsets.” It all starts with mindsets. Many of us have heard this topic by now: growth mindsets and fixed mindsets. We had to foundationally position it this way because if you come into any of this without first addressing your mindset, the battle’s already lost.

When you’re trying to work with folks around a culture of love or any of these topics… if we’re talking about building trust now, I said recently, think about your coworkers as good-intentioned folks. Inherently that requires a growth mindset to come to the table. Too often people try to jump ahead to tactics. People try to jump ahead to tool and process changes, and there are all these other things and pieces of training we can do.

If we skip the step of having people introspect, so they understand where they’re coming from and why they kind of have a block when it comes to thinking these ways, then you can sit through hours and hours of this kind of conversation.

For our readers, if this is not landing for you, you’re having a fixed mindset because you see the world one way, and if it doesn’t fit that it doesn’t make sense, then you automatically emotionally and intellectually reject it. I say that because I think the framework’s something we’re very proud of, but also something that’s held true time and time again.

If you start from anywhere in the middle, you can have some success. Real success comes from starting from what we say, mindsets, which affect our attitude and how we communicate, which are our behaviors and how we show up to others. Only then, when you’re focusing on those things for yourself, can you come to the table with real actions around building trust, inclusion, and empathy for people.

I want to go from directly to the challenges sometimes with working with organizations and individuals who haven’t yet had an opportunity to delve into introspection. In the world of business, we often reflect, but we don’t often introspect. Those are very different things.

When you’re finding you have leaders you’re working with, but also folks inside the organization, who don’t have this tool in their toolbox, how do you help people begin to develop that muscle around introspection?

(Chris) One of the first things we have to do is check with leadership. It’s important for people to understand when you don’t see leaders who have introspection, typically what you’ll find are victims in every situation. Either someone else didn’t do it right, someone else made them late, or someone else caused them to miss a deadline, it’s always someone else who did something they had no control over, and they are at the last end of it.

If you hear a lot of deflection and blaming, that’s typically a sign of a lack of introspection. When we are working with customers starting on this journey, oftentimes you’ll hear, “We’re good over here. It’s that other team… If everyone else changes I’ll be fine!”

That’s a classic, telltale sign of a lack of introspection. Often one of the first things we do is an event called Seneca Leaders. That’s a one-day offsite reset for leaders or people managers inside of an organization to spend the day focused on themselves.

The first topic we get into is introspection. We help them understand what it looks like, what it means, and what they have to do in order to get there. We like to give people that foundation and remind them of it throughout the day. As they hear our stories and peer stories in the room, they’re not sitting in a seat of judgment, thinking, “I don’t do that. I’m better than that. I never did that. Oh, I’m good.”

Instead, they put themselves in those stories and say, “Wait, have I ever made somebody feel that way? If I didn’t do it that way, has someone left me feeling that same way, or have I ever contributed to something that created confusion or chaos, or was unfair, or asked someone to do something I would’ve never done myself?”

It’s about helping leaders realize it’s easy to sit in the seat of judgment. It’s easy to be the hero in every story you find yourself in. Here’s a funny aside. Whenever I talk to people who are involved in religion, I ask, “Do you see yourself as the persecuted or the persecutor?”

If you only see yourself in the lives of the persecuted and you are sitting in a seat of authority or power in your organization, I’m always curious to know where you see yourself in these stories and scriptures you’re reading.

It’s easy for leaders, especially those who have been successful for their entire careers. They are capable of doing so much, they have so much potential, and they’ve gotten all the awards they’ve ever gone up for. To have these people stop and say, “Wait, maybe I’m not as great,” is usually hard to do solo.

In our session, we try and help take them off that pedestal and say, as humans, it’s okay to be imperfect, but also if you are a Tyra Banks fan, perfect is boring. If you watch America’s Next Top Model, who wants to be around a perfect person?

Thinking about it from that perspective and saying, your teams will resonate with you if they see you as someone they can approach, if they see you as someone who has thoughts, feelings, highs, lows, faults, mistakes, failures… sometimes the most connecting stories are those of failure, those of missing the mark, and those of having to learn the hard lessons over pure success where things come easy or feel like they come easy to you.

When it comes to introspection, we try and help organizations first understand the value of it. What does it look like and what does it not look like as you’re starting this journey? We want to make sure it’s approachable, it’s attainable, but it’s something that, as you are starting your own personal journey, you understand if you start with introspection, you’ll find a different path in every situation.

I love that.

(Jeff) To help people highlight… because a lot of times you talk about introspection and people just imagine meditating in a room with no end. The reality is, that’d be great, but in the workplace, it’s key to understand why we should bother with introspection.

The reality is, there’s so much power in self-awareness. You can almost draw a linear correlation between a lack of self-awareness and bad leadership.

It’s the power of self-awareness that brings us out of whatever funk we’re in. We’re not going to be perfect, but the worst is when we’re not and we don’t know it and we don’t see it, and we don’t bother to want to know it.

The reality about self-awareness though is we can have a leader who says, “I welcome feedback. My door’s open, give it to me. I can take it.” People may take you up on it, but the equation for self-awareness is what you think others think of you versus what they truly think of you.

When you’re getting all this feedback, you are getting what they’re actually thinking of you. If you’re not doing introspection, you’re not going to be able to use that data point properly to gain self-awareness.

What ends up happening is people give you feedback and you hear it with that fixed mindset. You hear it with one perspective that’s not combining it with work in yourself. What you give back is gaslighting, dismissing, and minimizing.

Slowly you realize your open door is open, but nobody’s walking through it and nobody wants to give you feedback. You’re sitting here still thinking you are the best leader in the world, and nobody’s telling you otherwise. It’s a spiral we see all too often of a lack of self-awareness. It’s core to the issue of what we talk about.

We don’t blast it upfront. If I could wave a magic wand and fix one thing, it’d be people’s real desire to want true self-awareness. If we truly desire it, it’ll show up in how we act. When things happen, we will consider if we’re the problem. That one moment is so powerful because you can ask, “What could I have done? There’s a lot of things I could have done.” Or when your team fails, “I’m the leader, that reflects me. What role did I play in this failure?”

It changes everything and everything comes so much easier. I can’t say enough about introspection along with self-awareness when it comes to these things.

I want to connect this to the idea of vulnerability. As a society, we have it that vulnerability equals weakness equals bad, equals not something we should be talking about in the workplace. Certainly, something a leader should never be, a leader should never show vulnerability. This myth is a firm part of our society. It’s something I am and I know you guys are about destroying.

This idea is deeply embedded in 20th-century as opposed to 21st-century ideas about what it means to be a leader. When you’re working with folks who may be less self-aware and who have this idea about vulnerability, how can we start thinking about that? I often talk about… I’ve had the opportunity to do a little bit of work with the U.S. Navy. One of the things these guys and gals will say all the time is that they have to be vulnerable with each other, and vulnerability takes strength.

They need to be able to tell the truth about what’s happening, and that takes strength. We have an opportunity to completely redefine this word, but it’s so connected with our mythology around what leaders are. How do you help people start to break that down for themselves?

(Jeff) I think vulnerability today is understood better than it ever has been before, which is a good thing. At the same time, when you start understanding concepts better, it’s also misunderstood and misused more.

It’s like organizational culture, talked about so much and completely misunderstood.

(Jeff) When it comes to vulnerability, it’s starting to get this wrap of sharing your deepest, darkest secrets and flooding the room with emotion and TMI. For some people, they’re thinking, “I’m going to be so vulnerable. I’m pouring myself out there.” People respond with, “Whoa, we don’t need all that…”

Do not bring that whole self to work.

(Jeff) There is a vulnerability in that, I’m not saying it’s not, and there are certain contexts and relationships where that is the essence of vulnerability. That said, it’s easier to understand vulnerability as owning up to mistakes, failures, and weaknesses. When you put it that way, you’re thinking, “Oh, well, that’s easy then…”

But Jeff, that’s so hard for us humans, we never want to say we’re wrong!

(Jeff) The reality is, in practice, we can all say to ourselves and in private, “I made a mistake, big deal.” I’m talking about in a context when people are affected by it, when people are even hurt by it… You made a decision where people worked weekends, lost family time, and experienced a negative impact

Are you able in that moment to not only say, “I’m the leader, so it’s on me,” but also say, “I did this and it affected you all, and I see that decision was hurtful, it was bad. I could’ve done better. I should’ve done better. I owe you more than that.”

These types of things where you honestly come to a space and are able to own… now I say own, not just fess up, but own a mistake. That to me is the core essence of true vulnerability.

That’s the difference. As we understand vulnerability, we’ve had leaders being coached to give what I call fake vulnerability, which is floodlighting people with emotion.

Sometimes it’s weaponized to get people to have sympathy for you. People will say, “I messed up and my life is so hard right now. My dog is dead…” It works because people will say, “I didn’t know you were dealing with all those things,” but you’re not gaining any ground.

You’re not moving the needle at all on your actual relationships and culture. When you can truly show a moment of understanding and almost a moment of commitment to being different or better, that’s when you make a difference.

(Chris) The other part of this equation is that we have organizations starting to introduce vulnerability into their walls and their leadership. There’s being vulnerable and there’s receiving vulnerability. What we’ve seen a lot of leadership teams go through who are newer on this train is, they don’t know how to receive it when people start bringing it out.

There is sensitivity to… we had this one organization where one of the senior leaders came to the small core team, and said, “I’m going to need some grace from you guys because I’m going through a separation with my husband and I’m feeling a lot of things.” What do you think the reaction was?

Oh, I’m so sorry.

(Chris) Nope.

The other way!

(Chris) It was “Oh, sorry to hear that. Let’s get back to the agenda we need to keep.” We might cringe at that, but sometimes, when you’re not used to receiving someone putting themselves out there inside of a team that historically is not known for that behavior, you see the discomfort immediately and then the desire to quickly move away from the discomfort.

People want to put the meeting back on track, to minimize that sort of difference in the room, and to get people back to comfort as quickly as possible. We end up dismissing those moments. We want to keep the peace and we end up staying positive toxically. It’s also about training leaders to understand they need to learn how to receive it.

Being human is not always giving it. That’s important, but when someone gives it to you, I hope your empathy muscle kicks in. It’s about your ability to listen, mute that sense of urgency leaders lead with, stop and give people space, and let the room do what it needs to do to make sure that person feels seen, heard, and understood.

That equation is important to understand because being vulnerable is critical, but receiving it is just as critical too. Otherwise, you have these misses when it comes to people wanting to do it again.

Or being completely unwilling to do it again.

I want to bring back an idea Jeff mentioned earlier about forgiveness. Often when people are being vulnerable, it isn’t necessarily, “I’m going through a hard thing, splitting up with my partner, or my folks are dying.” Often it’s, “You hurt me or that thing you did disrespected me.”

Then our opportunity is to honestly and truly forgive them. As humans looking back on our relationships, we know those places where trust has been broken and rebuilt are now the strongest places in our relationship, because we talked it through and made that new commitment to each other. “I did this thing and it created this in you. I own that and I’m sorry for that, and here’s what I can commit to now.”

We have such a hard time with owning our sh*t and then saying, “I am sorry for the impact it had.” We want to stay in the space of, “No, that’s not what I meant.” Well, I don’t give a shit what you meant. You hurt me. Being able to, as you said, Chris, exercise that empathy muscle and get what it is over there for them so then you can honestly, authentically, apologize and own it and make a new commitment going forward.

How do you help… my husband, for instance, grew up in a family in which that never happened. It’s hard for him. He’s still working on developing this muscle. How do we help people get better at lifting that weight? It’s so counterintuitive. It’s counter-human instinct. It’s all human spirit. It’s counter-human instinct.

(Jeff) Forgiveness is my favorite pillar out of the six. I think it’s the most unique one, and it made it into this core grouping because as we worked through all the things and tried to uncover what the keys to our comeback and success have been, we quickly realized unforgiveness is a huge root cause of so many things.

If you trace some of the issues back, you’d find, if we’re being honest, we’re making decisions with people in mind. These little factors, although they’re not overtly coming out, they’re based on how we feel about a person. I’ll assign someone to a project who I like, not someone who’s kind of upset me before, and I don’t see this as unforgiveness, but it is. These little micro-unforgiveness moments build up into large unforgiveness.

I’ve seen organizations where two high-seated leaders have been well-known to dislike each other for 30 years. They’ve been working there for 30 years. There are two warring factions in the organization. My question for them is, “Can you imagine how well this business could be doing if, over the last 30 years, these two hemispheres had been cooperating instead of completely isolating each other?”

All the energy getting poured into that animosity…

(Jeff) The reason I love forgiveness as a pillar is because it’s the least complicated out of all of them. I can talk to you for hours and hours about every single other one of these things. Trust is super complex. There are other little versions of it, but forgiveness is one of those that, when people feel like they understand what forgiveness is, they basically do understand.

It’s exactly what you think it is. When people ask, “Well, how do I get it?” The interesting thing is this is the one I lean on all five of the other pillars to accomplish, which is what makes it the hardest to do because you can rarely tackle forgiveness head-on. It’s the one pillar where you have to start somewhere else.

If there’s no trust, there’s no relationship. If you do not have empathy, there’s no inclusion. If there’s no vulnerability, for sure, forgiveness is a hard ask. If anything, it’s fake or one-sided. Often I don’t have a lot to add for people for forgiveness because the reality is, you have to forgive. You have to seek forgiveness and forgive others. As humans, it’s one of the hardest things to do, but there’s not only one way to do it.

The reality is, it relies on your relationship and the intensity of the conflict. It relies on who’s willing to come to where. It’s like high school drama. You have to find a way to meet by the lockers and hash it out. You have to care about something more than the fight. You have to want something bigger than the conflict, and you have to find common ground. At the end of the day, you have to find a way to truly find closure because it is a silent killer of actual business outcomes every single day.

(Chris) Practically speaking, when it comes to forgiveness, one of the best ways to experience it is if… I don’t know if you’ve ever been on the receiving end of an apology you didn’t expect, where someone felt they’d done something to you that harmed you in some way, and you never put those two things together and they still come out and apologize for it, chances are you’ll not see that person the same way ever again, whether you had anything against them or not.

Sometimes as leaders, you have to start an apology tour, so to speak, and start recognizing when you have put people back or given people the wrong instruction. It’s one thing to admit you made a mistake, it’s another thing to apologize for the mistake.

When you form those words and say, “Hey, I want to apologize to you because I gave you that instruction last week and I didn’t give you the complete information for it, and I know it’s probably sent you into a tizzy.”

Being on that side of the equation, chances are I’m going to give you more grace the next time. If I see something wrong, I’m going to be more apt to bring it forward. Then if there is another sort of situation, I’m more likely to forgive you again.

You can start these forgiveness trains by leading with an apology, recognizing it, and not waiting for it to get to a place where it’s a schism or this big sort of hemisphere situation. It doesn’t have to get to that state, but I think sometimes, as a leader taking it upon yourself to go and do that, it creates this other chain reaction where your team joins in.

Once you receive it, it’s easy to go and apologize because you realize it’s a good feeling and you can share the experience. Sometimes forgiveness can feel super religious. I cannot ever be on that level. Gandhi and Mother Teresa, you want me to be a saint? My name is not going to be in any Holy Book. That’s not who I am or what I get, but when you give people those sorts of…

Early on when you make a mistake, go and apologize to the person. If you think you did something wrong, go ahead and apologize.

Go own it and apologize for it.

(Chris) It could be a five-minute thing, a two-hour thing, or a 10-month thing. It could be two minutes.

How much energy are we going to save by cleaning it up in the moment?

(Chris) Exactly.

I could talk to you guys all day. This has been awesome, fun, and delightful, and I don’t want to create the world’s first 24-hour podcast, so I’m going to wrap it up here. Chris, and Jeff, thank you so much. Thank you for your wisdom, your insights, and your experience. I’m truly blessed to be here with you both today.

(Chris) Awesome, thank you, Janine.

(Jeff) It was a pleasure.

Awesome. I am Janine Hamner Holman, and this has been The Cost of Not Paying Attention. Remember, great leaders make great teams. Until next time.

Important Links

Love as a Business Strategy book

Psychological Safety with Amy Edmondson

Love as a Business Strategy podcast

About Jeff Ma and Chris Pitre

Coming up through a decade in the gaming industry, Jeff Ma eventually found his niche in project management and agile coaching at Softway. As he continued working with teams and clients in scrum and agile environments, however, he started seeing the stronger underlying importance of culture in truly high-performing teams.

Pushed by a combination of his own introspection, feedback from his colleagues, and a whole lot of uncomfortable practice, Jeff shifted head-first into a new mission he shares with his team: to bring humanity back to the workplace.

Nowadays, he’s hyper-focused on helping people find a workplace culture that allows them to be their whole selves, their best selves. Jeff is leading the development of various products and tools that are crafted with a culture of love at its center.

As a co-facilitator of Seneca Leaders and the other experiences in the Seneca suite, he is also connecting and transforming leaders around the world directly, helping them improve their mindsets, behaviors, and leadership capabilities.

Chris Pitre is a student of the world and enjoys anthropology, history, travel, and culinary experiences. His interest in global cultures naturally led him to travel around the world co-leading change management and leadership through Seneca, Softway’s workplace culture program.

Prior to his role at Culture+ and Softway, Chris managed global business development for the creative and automation practice within Astadia, an IT service management company. There, his clients were in the telecommunications, technology, and healthcare industries.

He has experience in digital and social media, marketing, and communications. Chris is a native Houstonian who loves everything Beyoncé. He has a B.A. in Business Administration from The George Washington University in Washington, D.C.